By: Antony Sutton

No-one can be quite sure when Christianity first reached the Indonesian archipelago. The earliest hint comes from a kind of handbook for early travelling Christians. Though published in the twelfth century in Egypt by an Armenian historian and geographer, the idea of a manuscript providing information about churches and monasteries in Africa and Asia had been around for several centuries and many had been used as source material by Salih.

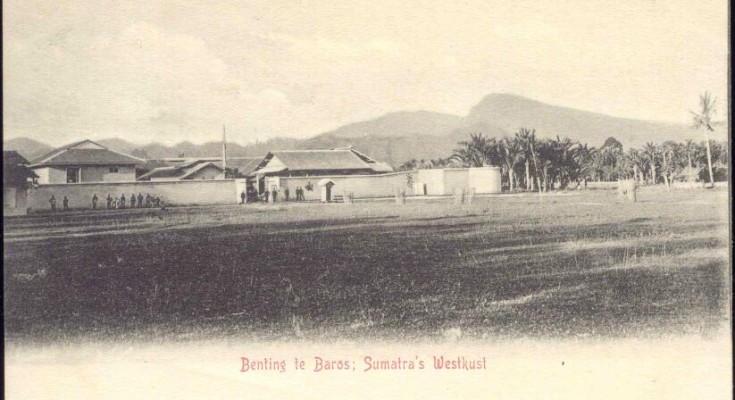

The Armenian had mentioned a community of Nestorian Christians living in Fashur, trading in the highly prized camphor. The actual location of Fashur in the texts is vague but there was a port called Fanshur which was famous for camphor and it has been placed on the west coast of Sumatra near Baros, itself a town of some importance as it would receive many traders from southern India who would stop off there on their way to and from other entrepots.

Indeed, Baros was so well known that the Greek historian Ptolemy was aware of its existence in the first century AD.

With the vaguest of clues putting a timescale on Christians arriving in Baros and beyond, except for that one small clue there is little else to suggest a presence. Salih mentions a church, the Pure Virgin Mary, but that’s where the trail runs dry.

Close to Baros lay the port of Lobu Tua and local Batak folklore suggests the port was built by foreign traders. Excavations suggests Lobu Tua dates from the 9th century, some 800 years after Ptolemy had first identified the site. Were those foreign traders early Christians serving the early fleets from the Malabar Coast as well as the Bataks in the hinterland?

By the end of the 13th century there were sources suggesting Dabbagh, the name for Sumatra and Java at the time, had its own bishop.

The famous Italian explorer Marco Polo also travelled round that area of North Sumatra but says little of Baros, by then no longer the power it had once been.

In the middle of the 14th century a French priest, while travelling home from China, recalled meeting some Christians both at the court of Majapahit and Palembang. A few isolated scraps of information passed down through time give the merest hint of the possibility that come the Portuguese and Dutch explorers from 1500 onwards their ideas of salvation may not have been totally unknown to pockets of the populace.

Halmahera is very far from anywhere these days. But its location next to the original spice islands of Tidore and Ternate means that its history is a very colourful one indeed. The tiny twin islands were forever at each other’s throats with fighting, sometimes spilling over to the much larger Halmahera.

In 1529, perhaps emboldened by the presence of some Spanish ships, the king of Halmehera conquered some land Ternate considered its own. Four years later Ternate fought back. Leading members of the Halmahera community were shocked by the treatment their fellow settlers had received at the hands of the returning Ternateans, taking their complaints to a prominent Portuguese businessman who advised them to convert to Christianity then seek the protection of the Portuguese.

This small, local dispute and the subsequent conversions was the start of the Roman Catholic community in what was to become Indonesia. It wasn’t all plain sailing of course with the various islands forever feuding. As it happened, the Portuguese were unable to protect the converts and many apostatized in the face of continuing aggression. From then on Christianity secured a firm foothold in the islands and even today Jakarta, amid its hustle, bustle and gridlock, boasts a number of old churches that have a tale or two lying in wait in their pews.

Geraja Sion (Jalan Pangeran Jayakarta No 1, Kota), also known as the Portuguese Church, is the oldest church in Jakarta. Dating back to the late 17th century it was originally constructed to attract slaves of Bengali, Gujerati and Malay origin who had been received Portuguese names on being granted their ‘freedom’ and left to make their own way in the world. They were allowed to worship, on condition they converted from Catholicism to Protestantism and as long as they didn’t use Dutch. So for centuries they worshipped in Portuguese, for many the only common language binding them.

Take Tugu Church, built in 1747, for example. There was something almost Amish in the way local residents hung on to traditional clothes, sprinkled their language with Portuguese and showed great pride in their music, keroncong, which has its roots in the Islamic occupation of the Iberian peninsula, in the face of Dutch power and increasing Indonesian nationalism at the turn of the 20th century.

In 1811 the British invasion force, led by Stamford Raffles, would have marched past the tiny church after coming ashore at Cilicing and you can imagine Raffles, given his fascination with all things South East Asian, pausing for a moment or two admiring the little chapel that was nearly 150 years old, perhaps taking in tombstones dating back a century or more.

Its appeal lies in its simplicity. A small, single-storied building almost hidden from the main road by a few trees, the whitewashed walls house a cosy congregation of a few dozen worshippers. Batak, Manadoese, Sighenese, Florentenes among others flock regularly north, fighting the industrial traffic that clogs the narrow, potholed lanes outside.

Quaint is a word rarely associated with Jakarta but with the Anglican Church it seems apt. This pocket sized church was built by the British in 1821 and tells its tale through fading tombstones removed from their original location and added to the inside walls.

There is the story of a Prisoner of War, held by the Japanese at the Tanjung Priok docks during the Second World War, who somehow found the time to make stained glass windows.

(First published in Jakarta Expat)