By: Ari Ernesto Purnama

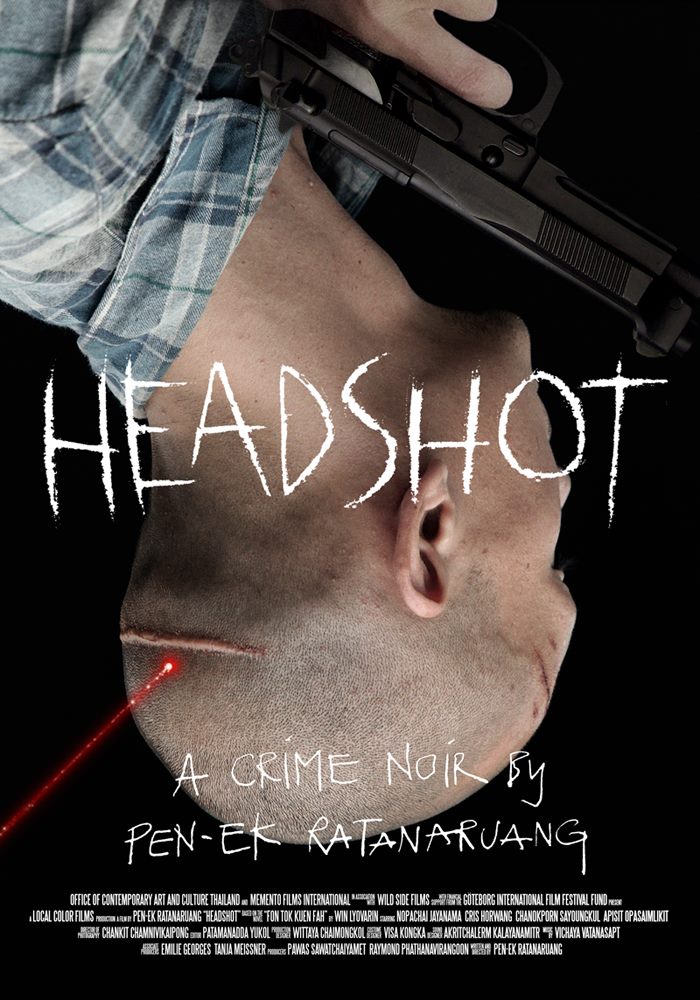

A Review of Headshot (Pen-Ek Ratanaruang, 2011) at CinemAsia Film Festival, De Balie 4-8 April, Amsterdam

Last Saturday at the CinemAsia film festival (De Balie, Amsterdam) was the premiere of Headshot, the latest film made by the internationally reputed Thai filmmaker Pen-Ek Ratanaruang. Ever since the trailer came out, I have anticipated the day of watching this first attempt at crime drama by Ratanaruang firsthand.

Headshot, an Action Flick Made Difficult?

Headshot tells the story of a cop turned a hitman turned a Buddhist monk turned a hitman again, but this is not all. There’s so much more to it than one could expect from a crime thriller. Tul, a plain clothed police officer in a big city somewhere in Thailand is framed by a crooked politician, because he refuses to compromise by not giving up the case that involves a high ranking government official. From there the turbulent rollercoaster ride of chase and run begins.

He gets incarcerated because of this set up. Just midway through his prison sentence, a character named DEMON approaches Tul for a job that he never expected: becoming a hitman. During one major assignment to kill a powerful man, Tul gets shot in the head. He is in a coma for three months. But when he wakes up, his world is turned upside down. Visually and metaphorically that is. Not only is his vision inverted 180 degrees, but he finds himself hunted down by those who seek revenge on behalf of this powerful man. A girl saves his life several times, but her presence turns his world even more upside down.

Headshot has all those tropes that one would find in a film noir[1]: complex narrative timeline, the presence of a femme fatale, the grim depiction of the urban underworld, and obviously the portrayal of a feeble-minded male protagonist who is pressed to undertake a morally correct decision in a corrupted world. And often than not, the male protagonist is associated with professional detection, whether as a private investigator or a cop (remember the plain clothed cop in Fritz Lang’s The Big Heat?). Contrary to what people say that Headshot is an action film, Headshot does not really showcase a great number of showdowns or gun fights. When there are scenes that involve shooting, it mostly lasts for a couple of seconds and they usually function not as point-turners but as scenic textures, meaning that even when the shootings do not take place, we will still get the idea that the male protagonist is wanted by the perpetrators.

It suffices to say that actions scenes in Headshot do take the centre stage. So, I can conclude here that perhaps Headshot heads toward the direction of a crime thriller with the soul of a puzzle film such as Memento even though it doesn’t touch the subject of a memory game or amnesia in its story development as the latter does. Yet, Ratanaruang slips in one vital element that makes Headshot an atypical crime noir, and that is the principal view on self-determination taught in Theravada Buddhism.

In this school of Buddhism, practiced in many Southeast Asian countries (Thailand, Myanmar, Cambodia and Laos) every individual is personally responsible for their own self-awakening and liberation, as they are the ones that were responsible for their own actions and consequences. Simply learning or believing in the true nature of reality as expounded by the Buddha is not enough, the awakening can only be achieved through direct experience and personal realization. In Theravada belief, Buddhas, gods or deities are incapable of giving a human being the awakening or lifting them from the repeated cycle of birth, illness, aging and death. In Headshot, Tul is exposed to a scientific paper that explains the theory of evolution regarding the survival of “evil” genes, but this does not mean anything to him unless he experiences himself what it feels like to be evil. In the end, when he becomes a Buddhist monk to seek refuge, he realizes that the true nature of “evil” is not hard-wired biologically, but it is self-imposed and one suffers the consequences tremendously if one does not liberate him/herself from this cycle of ‘evil’ deeds.

Headshot: Visual Extravagance Here, There & Everywhere

Ratanaruang matches the subject matter of the film with dark muted color tones interlocked with the striking inverted shots of Tul’s vision that capture his oblique world. His long-time cinematographer Chankit Chamnivikaipong does a really fine job here in combining some fixed shots with hand-held cinema-verité styled shots. One scene in particular being when Tul escapes the chase in a Buddhist monastery. I think the striking visual style serves to enhance the brooding atmosphere of Tul’s world since he gets shot in the head. But it does so in a subservient way, therefore the visual style does not really call attention to itself. Overall, I think stylistically the film works effectively with the narrative undertaking to create a balanced piece of cinematic work.

Headshot, Between the Popular and the Art

Pen-ek Ratanaruang was born in Bangkok in 1962. He studied Art History at the Pratt Institute in New York and worked as an illustrator and designer before moving on to directing commercials and films.

Along with Apichatpong “Joe” Weerasethakul and Wisit Sasanatieng, he is considered as one of the leading figures of the Thai “new wave” cinema. His filmography includes 6ixtynin9 (1999), A Transistor Love Story (2001), Last Life in the Universe (2003), Invisible Waves (2006), Ploy (2007), and Nymph (2009).

Ratanaruang’s films manage to oscillate between the popular and the art, meaning that they are on the one hand screened at prestigious international film festivals and received critical acclamation, but they are also screened at major theatres in Thailand and favored by local audiences. Yet, only a limited audience could get access to his films outside these two arenas. Find out more about this film on the website of Headshot.

[1] Film Noir is a cinematic term used primarily to describe stylish Hollywood crime dramas, particularly those that emphasize cynical attitudes and sexual motivations. Hollywood’s classic film noir period is generally regarded as extending from the early 1940s to the late 1950s with canonical examples such as Fritz Lang’s The Big Heat, Howard Hawk’s The Big Sleep and Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity.