By: Sue Ingham

Indonesia’s participation in the Venice Biennale in 2013 sought a place for Indonesian contemporary art within the international dialogue of cosmopolitan art exhibitions. The Indonesian pavilion proved to be popular with visitors and was deemed a success. Yet the works were supposedly representing Indonesia raised difficult issues of identity.

In simple terms, cosmopolitanism means being ‘a citizen of the world’, exchanging ideas and sharing values. Yet closely associated with this concept is another term, globalisation, which can have a darker side. As with economic globalisation, developments in technology and communication have influenced the visual arts and internationalised the exhibition and sale of art. Art practitioners, theorists and institutions have expanded their networks and influenced each other, creating an international language of art now called ‘contemporary’. Indonesian artists have shown they are familiar with the forms of international exhibitions and have worked with performance, installation and other contemporary media. Their works share a number of concerns with the rest of the world, such as damage to the environment, violence and discrimination against minorities. If, on the one hand, Indonesian contemporary art is similar to international art in both form and content, how is a sense of local identity retained? On the other hand, if artists simply apply traditional and familiar forms such as wayang puppets or Balinese dancers as symbols of being Indonesian, they ignore the complex issues of living in the modern society that is Indonesia today. To negotiate cosmopolitan art circles and find a voice in the dominant global art dialogue, Indonesian artists needed to find ways of expressing their local experience without the use of trite symbols.

Venice Biennale

The Venice Biennale was the first regular survey of international contemporary art. The City of Venice chose the Biennale in 1895 as a ceremony to mark the historic unification of Italy and the Biennale continued in order to raise the profile of the city, attract tourists and finance restoration projects. Venice has become the template for the international exhibitions, biennales and triennials that are so prevalent today. They tend to share similar aims, such as international recognition for their culture and to stimulate economic and diplomatic ties, while participating artists gain exposure and validation of their work.

Belated recognition

Awareness of modern and contemporary art inside Indonesia had been slow in coming. The Suharto regime suppressed cultural experimentation and favoured the traditional arts, considered of greater value for tourism and commercial purposes. Indonesian participation in the Venice Biennale was rare before the end of the 20th century. But the Eurocentrism of the Biennale itself was a contributing factor and even though Asian art is now regularly exhibited, the majority of the national pavilions in the Giardini, the Venetian public gardens used for the Biennale, are still European. Before the 1990s, Affandi was the only Indonesian modern artist to achieve true international recognition. In 1954 he was invited to participate in the Venice Biennale where he was awarded a prize. It was to be nearly fifty years before another Indonesian artist was invited again.

Globetrotting

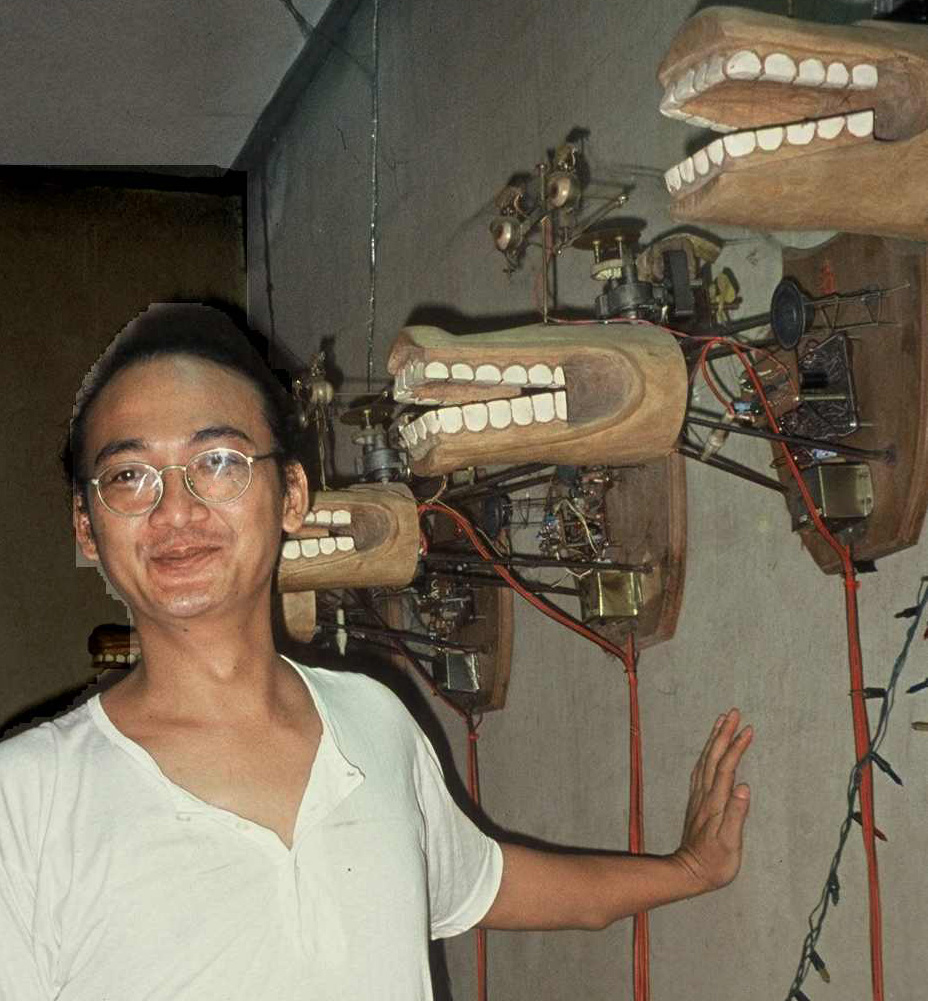

In 2003 the Biennale Director, Francesco Bonami, and the Curator, Hou Hanru, invited Heri Dono to participate in the section titled Z.O.U. or Zone of Urgency for the 50th Biennale of Venice. By then Heri Dono had established a career as a globetrotting contemporary artist, the first of his generation to do so. His career began in 1990 with an opportune residency in Switzerland, when there was little outlet for his work in Indonesia. This was followed by residencies in Britain, Australia and other countries. He became the epitome of the cosmopolitan artist, with the skills to navigate the requirements of international shows, such as speaking English, the language of globalisation, and being able to address a curatorial brief.

Heri Dono with his work, “Watching the Marginalised People”

Heri Dono with his work, “Watching the Marginalised People”

While biennales favour local identity and the exhibition of art according to the country of origin, there is a contradictory pressure to have works conform to a universal standard of contemporary art. Heri’s work seems to have found a precious balance between local identity and the language of global art by addressing an international issue while retaining an Indonesian point of view. His work in the 50th Biennale of Venice was titled Trojan Cow and was a mixed media painting beside a large cow-puppet. The painting depicted George W. Bush as Superman in cowboy gear alongside Tony Blair as Batman shooting at an oil can with Saddam Hussein’s head on it. It was presented as a shadow play drama performed for the people, here represented by the dumb cow. Heri disguised his criticism of the invasion of Iraq with humour, using a surreal combination of Indonesian wayang figures and internationally-known comic strip characters. The hybrid references are a bitter joke, a technique to express the unpopularity of the actions of the international powers, but doing so in a very Javanese way that avoids confrontation and conflict.

Self-funded

While Heri was invited by the Biennale organisers and exhibited in the Arsenale, one of the official exhibition areas, another group of Indonesian artists were mounting an exhibition at a venue elsewhere in the city. Since the late 1990s some Indonesian artists had been participating in a few of the many independent satellite events that accompany the Biennale. Most were privately initiated and largely self-funded with little, if any, assistance from the Indonesian government. According to the curator of this 2003 satellite exhibition, Amir Sidharta, the Indonesian Ministry of Tourism and Culture was enthusiastic when approached and agreed to provide the airfares for exhibiting artists. But somehow the money ‘disappeared.’ Some artists withdrew, including Mella Jaarsma, and those who attended had to fund themselves or organise sponsorship. Arahmaiani, for example, was funded by the Ochs and Preuss gallery that represented her in Berlin. This has remained the pattern for Indonesian art in international exhibitions – exposure overseas is nearly always the result of individual effort and private sponsorship, not government support.

In 2013 Indonesia, as a country, was invited for the first time by the Biennale Foundation to mount a national pavilion in the Arsenale. It was a significant step, but once again initiated by private sponsorship. The driving energies behind the project were Restu Imansari Kusumaningrum, director of the arts consultancy Bumi Purnati Indonesia, and Carla Bianpoen, an independent art journalist. Carla co-curated the exhibition with Rifky Effendy, an independent curator, and they were assisted by a number of Indonesian as well as Italian advisors. It was a long and arduous process to convince the Indonesian government that it was important Indonesia be represented in Venice. The Ministry for Tourism and the Creative Economy eventually allocated money for the rent of the Arsenale space, the first serious funding involvement by the government. But rent is a small portion of the budget and funding for the project has remained a major problem.

Sakti

Five visual artists – Albert Yonathan Setyawan, Sri Astari Rasjid, Eko Nugroho, Entang Wiharso, Titarubi – and the musician Rahayu Supanggah were selected to mount works in the pavilion around the central theme of Sakti. Sakti is a traditional Hindu concept of regeneration and female creative energy that, according to the curatorial essay, had a contemporary meaning in ‘the creative struggle inherent in Indonesian art and life’. Themes are considered necessary to connect disparate works and gain support for such projects. But the concept that Indonesia’s ‘rich cultural heritage’ would be given meaning in ‘contemporary art practice’ as also stated by the curators, met with varying degrees of success. Some of the works derived a sense of Indonesian identity from traditional references to temples and the Queen of the South Seas while other works belonged almost entirely to the vocabulary of international art with barely a recognisable Indonesian reference, apart from the notes accompanying them.

In Venice: L – R: Albert Yonathan, Sri Astari, Carla Boenpoen, Achille Bonito Oliva, who was a consultant, amongst others, for the pavilion, Rifky Effendy, Titarubi and Entang Wiharso.

SAKTI, Indonesia National Pavilion, ARSENALE, 55th International Exhibition, La Biennale de Venezia

A comparison of the works by two of the artists, both women, illustrates the push and pull between local identity and global community. One work used only traditional forms while the other was ‘biennale art’ in which it was difficult to detect any particular Indonesian reference at all. In Astari Rashid’s installation, Pendopo: Dancing the Wild Sea, the Bed Oyo dancers at the entrance to the Javanese pendopo house are decorative, ethnographic objects. They are supposed to refer to the Queen of the South Seas and illustrate Sakti, the female power, but it is difficult to detect any transformation of tradition into contemporary meaning. The dancers remain conventional symbols of Indonesian culture and static signifiers of Indonesian identity.

On the other hand, Titarubi in her installation, The Shadow of Surrender, worked entirely with the forms and content familiar to international audiences. Her artist’s statement claimed that the benches made from burnt wood with overly large blank books are a reference to her experience at school while the large charcoal drawings of a burnt forest on the walls referred to environmental damage. These forms and their meaning are so familiar that they can be found elsewhere in this same Biennale. A Costa Rican artist used desks, and books were used by a Brazilian. If Titan is referring to a contemporary Indonesian experience, it is lost in the all-too-familiar forms of installation art in international exhibition.

Astari Rashid, “Pendopo: Dancing the Wild Sea”

Astari Rashid, “Pendopo: Dancing the Wild Sea”

Titarubi, “Shadow of Surrender”

Titarubi, “Shadow of Surrender”

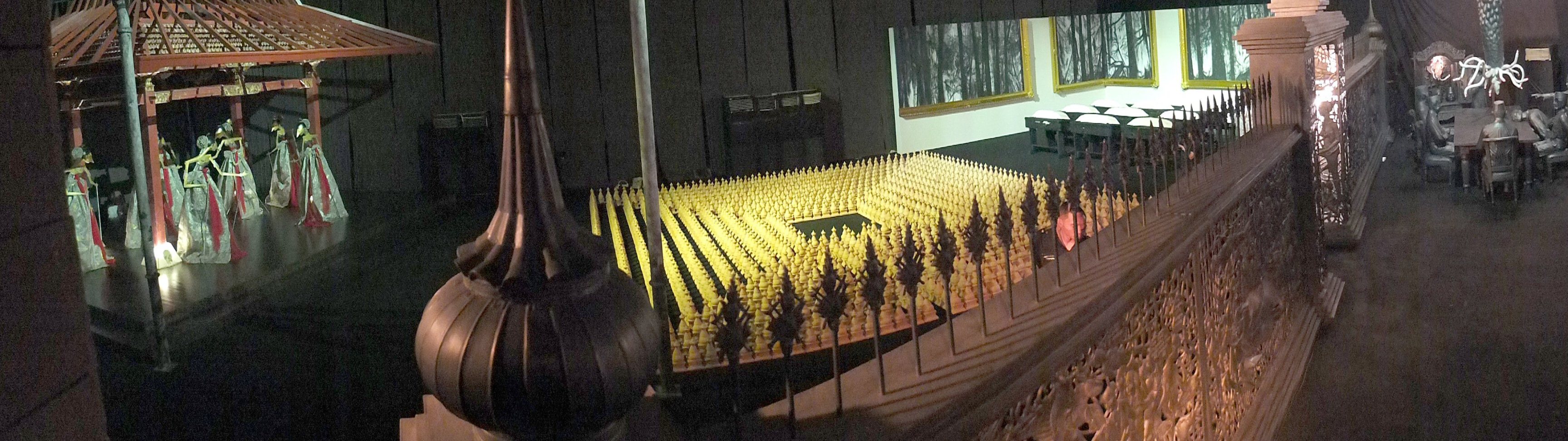

Albert Yonathan Setyawan Cosmic Labyrinth: The Silent Path was another installation, consisting of a thousand ceramic stupas laid out in a shape reminiscent of Borobudur. The curatorial essay states that the work was ‘inspired by other houses of prayer’ and ‘reflected the plurality of Indonesian society throughout the ages.’ But this is not apparent in the work. The forms are well-known references to Javanese temples and, with the very familiar form of repeated shapes laid out in a pattern, the work is designed for an international biennale audience.

Eko Nugroho’s bamboo raft, Penghasut Badai-Badai (Instigator of Storms), was perhaps the most transgressive work in the Indonesian pavilion. It is claimed that the figures on the raft symbolise the ability of the Indonesian people to survive amidst overwhelming political, social and religious challenges, and that this is a ‘feat of Sakti’. But the use of old oil barrels with fantastical figures and shapes stems more from Eko’s surreal comic strips than suggesting uplifting creativity. There is a cynicism and a challenge in this work that is incompatible with the benign and spiritual theme.

Albert Yonathan Setyawan, “Cosmic Labyrinth: The Silent Path”

Albert Yonathan Setyawan, “Cosmic Labyrinth: The Silent Path”

Eko Nugroho, “Penghasut Badai-Badai (Instigator of Storms)”

Eko Nugroho, “Penghasut Badai-Badai (Instigator of Storms)”

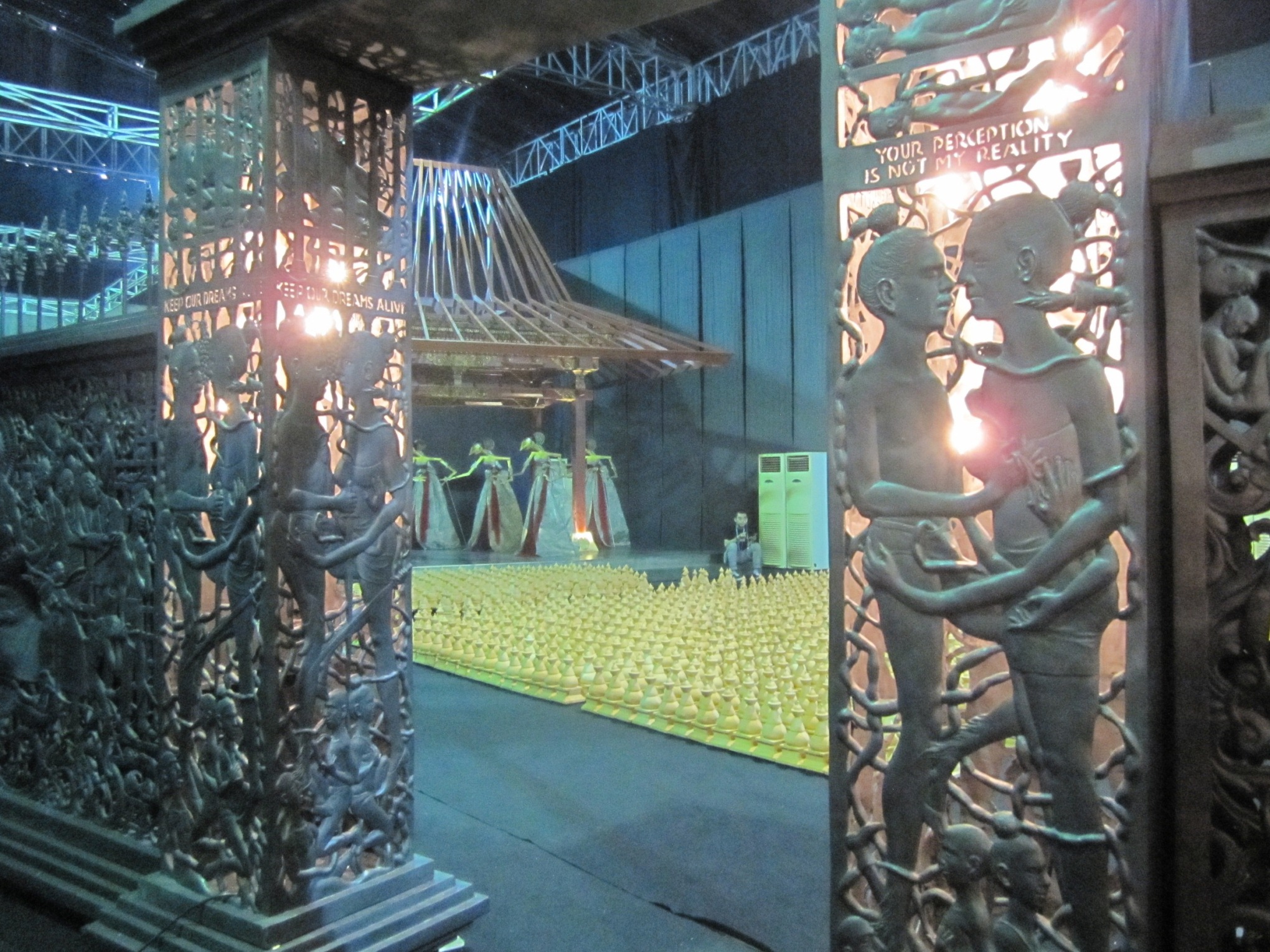

Entang Wiharso, “The Indonesian: No Time to Hide”

Entang Wiharso, “The Indonesian: No Time to Hide”

Detail of Entang Wiharso, “The Indonesian: No Time to Hide”

Detail of Entang Wiharso, “The Indonesian: No Time to Hide”

Contemporary meaning

Of all the works, Entang Wiharso’s The Indonesian: No Time to Hide, successfully draws on the traditions of the past to comment on contemporary life in Indonesia. Entang’s work references the narrative reliefs on Hindu temples such as Prambanan in Central Java but inserts contemporary relationships and disturbing meanings in what look like traditional forms. A wall of reliefs surrounds four of the installations intersected by an entrance gateway into the exhibition. Outside the wall are the figures of past and present presidents of Indonesia seated at a table, one abject figure lying across the table from them. At the gate a male and female nude face one another under an inscription that reads ‘Your perception is not my reality’. Are they Adam and Eve? Questions are raised by all of the figures in the relief. They appear to represent love, deceit, politics and history but with unexpected changes of scale and eruptions of organic shapes. The meaning is obscure and if the reference is to mythology, these are myths with a contemporary connotation. Even the medium is contradictory. The work has the impressive scale and solemnity of metal yet is not as solid as the bronze, aluminium and graphite construction implies. Volcanic ash has been incorporated into it, perhaps from the eruption of Mount Merapi outside Yogyakarta in 2010, which could be a suggestion of potential violence. This is an ambitious work from a sophisticated artist who can blend personal meaning and contemporary Indonesian references in an installation that is understood as a part of an international dialogue.

The pavilion was ‘staged’ with gamelan music by Rahayu Supanggah and dramatic lighting effects. Overall, the Indonesian pavilion held its own among the many installations and national pavilions of the Biennale. This was the primary aim of the curators: to show that Indonesia could take its place ‘on the global map’ and ‘that the world would take due note’, as Carla Bianpoen wrote. But as Alia Swastika asked in her review in the Jakarta Globe, ‘should Indonesian art be reduced to nostalgic symbols rather than offering a critical perspective on the current national and even international situation’? National identity remains one of the many issues that surround biennales. But to address that issue in some meaningful way, a work should also engage the viewer at a personal and subconscious level – and this is rare.

Sue Ingham obtained her PhD from the University of NSW College of Fine Arts in 2008 on Indonesian contemporary art. Her website http://inghaminindonesia.com/ presents her research material and current events. Images of the Indonesian pavilion at the Venice Biennale were provided by Bumi Purnati Indonesia.