By: Emma Kwee

Time for another addition to our ever growing ‘family’ of cross-cultural couples. Read about the other cross-cultural couples that shared their story. Sita and Oka met in 1984 in The Hague, the Netherlands. They live on Bali and have two stunning children, Bika and Amba. Sita tells us how she met her husband and how their Balbel (Bali-Belanda) marriage developed. Sita had so much to share that we had to edit this down, by half, and still ended up with over 8 pages. We will offer her valuable insights in several blogs during the coming few weeks.

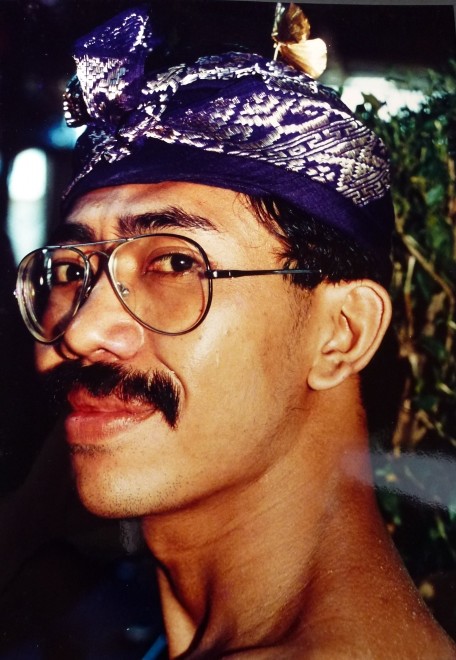

Can you introduce yourself to our readers? Sita: ‘I am Sita van Bemmelen, born in 1954, Groningen, the Netherlands. When my father was in college, he learned Sanskrit, just for the fun of it. That is why my name is not a regular Dutch name: Sita is the main female character in the Indian epos Rayamana. Perhaps I was destined to end up marrying a Hindu, never mind he is not from India, but from Bali, Indonesia. My husband is Ida Bagus Oka Sumarjaya Pidada, born in 1958, Klungkung, Bali. We have two beautiful and clever Balbel daughters: Ida Ayu Amba Mathilde (1991) and Ida Ayu Bika Alice (1994), both born in Jakarta. Excuse me for displaying parental pride!’

How did you meet? Sita:’I met my husband in 1984 in The Hague, the Netherlands. At the time, he had been living in the Netherlands already for five years, while working for the accounting department of the municipal Electricity Company. Of course, he was fluent in Dutch, because he had to use this language with his colleagues and the company’s customers. We did not fall in love right away. When I met Oka for the first time through a mutual friend, he had just moved out of the apartment that he had shared with his first Dutch wife and was still in the process of coping with his separation from her.

Over the next one and a half years, we met several times in the company of our friend and others. Oka did not seem very happy. I remember teasing him because of this: ‘why don’t you just go back to Bali?’ Later he told me that an older relative of him in Bali for whom he had great respect, had urged him not to return to Bali empty-handed. He should at least bring home a diploma. He had taken this advice seriously and worked hard for a certificate in accountancy and business administration, which kept him busy several evenings a week after his working day.’

And how did your relationship develop? Sita: ‘One day, to my surprise, he showed that he was interested in more than a casual friendship with me. Meanwhile I had come to admire him for his stamina to stick it out in the Netherlands and I found him quite good-looking too, so suddenly I looked at him with different eyes and thought ‘why not? Let’s give it try.’

It may sound not a very romantic start of relationship and indeed, it wasn’t. For example, we immediately talked about ‘basics’, whether we wanted to have children. This was an important issue for Oka. I could assure him that I also wished to raise a family. On my part, I wanted to know why he was interested in a relationship with me. His answer: ‘because you have been to Indonesia and are interested in my country’. Fortunately, Cupido arrived on the scene very soon and aimed his arrows expertly.

How serious Oka was about ‘us’ soon became clear, because he wanted to meet my parents. This was new to me. My former boyfriends had never wanted to meet my parents in the beginning of the relationship. So I took him to my parents’ place a few weeks later. To his dismay, my father, who had seen not a few boyfriends of mine coming and going, did not pay much attention to him.

On a second visit, Oka planted himself in front of my father, looked him straight in the eye and, pointing at his chest, said: ‘I am Sita’s boyfriend!’ From then on, they developed a close friendship.

Sharing a keen interest in chess helped bringing them together. My mother felt at ease with him as well. Perhaps because my grandmother not only had more Indonesian than Dutch blood running through her veins, but also conducted herself in the reserved manner typical of Eurasian and Indonesian women. When I took off five months later to conduct research in Indonesia for a year, Oka visited my parents several times on his own initiative during my absence.

I think we made a fortunate start in many respects. First, we never had an acute communication problem as so many other mixed-married couples in the beginning, because Oka already spoke Dutch fluently when we met. Dutch is the language we still use between the two of us until today, although we already live in Indonesia since 1991 and I have become fluent in Indonesian a long time ago. I feel that being able to use my mother language with my husband at home gives me a ‘place to rest’ mentally on a daily basis.

This has been particularly important during my first years in Indonesia – we moved to Jakarta in 1991 – because it was exhausting having to listen to and speak Indonesian in my workplace and coping with the unfamiliar and often confusing behavior of others towards me. It is also nice, that we can share our experiences and thoughts in our own private language space.

I think my husband feels likewise, although at times he has felt uncomfortable with this arrangement, because he cannot express himself as easily in Dutch as I do. On the other hand, using Indonesian was not really a good alternative for him, because his first language is Balinese, a language I have not yet been able to master.

People in Indonesia are often curious how I met my Balinese husband. Usually they assume that I met him during a holiday on the island and some suggest that perhaps he was my handsome tourist guide?”

I think we have been lucky that we started on a different footing. I have seen not a few mixed marriages between foreign women and Balinese men end in divorce, because after a few years of insufficient understanding of the other’s behavior and values wrecked the relationship. I do not want to imply that our marriage has been smooth all the way: we were still in for the occasional unpleasant surprise. But my husband and I at least enjoyed the comparative initial advantage that both of us were already familiar with the country of the other and the way of life plus mindset of its population.’

So, what makes your marriage work? Sita: ‘Of course, mixed-married couples cannot plan what they are heading for when they wed, if they are young. But is important to discuss which basic values each of us holds high. It helps to become aware of values and goals we can share and, more importantly, differences that we need to work out together or respect if common ground cannot be found. We agreed upon having children from the start, which I think was a crucial understanding in our relationship. We did not discuss at the time where we wanted to live in the future, but when I was given the opportunity to work in Jakarta several years later, the matter was quickly settled between the two of us. Although Oka had an excellent job at the time with good prospects, he felt something was missing: a challenge. He also missed his family. I think that both of us like challenges and supporting each other in facing these is what makes us tick.’

How did your surroundings react? Sita: ‘The attitude of the family may be a crucial factor in determining the fate of a mixed-marriage. My parents embraced my husband as a member of the family after they came to know him. Understandably, my husband feared that his family might not be so easily persuaded to accept me. They had been very fond of his first Dutch wife and regretted his separation from her.

Oka introduced me to his eldest brother when we went to Jakarta together for the first time. He did this on purpose, hoping that if his eldest brother would accept me, the rest of the family in Bali might follow suit. His eldest brother saw how much we were in love and waving his arms in circles while talking about butterflies, gave us his blessing. When we visited Bali later in the month, my husband’s mother and other relatives understandably remained somewhat distant, obviously having reservations about our relationship. Some were honest with me, saying that in their opinion my husband had better marry a Balinese woman after his first marriage with a Dutch woman had failed. I felt offended, because I was not the same person as Oka’s first wife. But I also understood their anxiety, so I let these remarks go.

We did not intend to marry according to Hindu belief on this first visit. To my surprise, when we came to Bali again two years later, my husband’s eldest brother ‘summoned’ my husband to formalize our relationship. Clearly, he thought it improper for us to go on living together as an unmarried couple in the Netherlands. On our next visit, in April 1988, we married in the family temple in the town of Klungkung, in the presence of the members of the entire extended family of my husband. My parents, two of my three siblings, an uncle and aunt of mine and several friends had come with us to attend the ceremony. Biding time had proved to be prudent to bring around all parties. It had not been difficult, because the two of us also had needed that time to find out whether we really wanted to get married.’

What were the biggest challenges you and Oka had to overcome? Sita: ‘We all have certain expectations about what we would like our marriage to be and more in particular what we expect from our partner. Unfortunately, we often only realize what these expectations are until it becomes clear that our partner does not ‘live up’ to some of these.

I like share to following example of my own experience regarding something that might perhaps looks trivial: spending time together and holidays. My parents used to take us on vacation every year when we were children, most of to Italy. I have very fond memories of those vacations: the beautiful towns and cities, the beach, the lakes, the Italian food. While my husband and I were still with the two of us and living in Holland we also went on long vacations: to Bali! We toured the island from east to west and north to south and I loved it. When living in Jakarta, we regularly escaped the hot and crowded city for a weekend in the Puncak with the children and we went to Bali more often.

But once my husband had come back to his beloved island in 1996, he lost interest in traveling. But I wanted our children to see more of the world! So I tried hard to coax my husband to come with us, if only for short vacations to Java. The few times he came with us were not a success, because he could not detach himself from his work or, finally ‘forced’ to take it easy, fell ill. I felt hugely annoyed by this, seeing my idea of family life of which going on vacation together turned out to be a vital part, shattered. It helped when I finally came to realize, that he was not raised in a culture where taking a vacation is normal. Bali is known as the island where people often take days off from work (Bali – Banyak Libur), but they do so to attend to their religious duties. The past few years, I have abstained from trying to persuade him to come with us. The three of us go and he stays in what he calls the best hotel in Bali: home. I still deplore that I cannot share my love of traveling with him, but there are other, more important things in life, that we do share.”

Are there any differences in religious beliefs? Sita: “I just mentioned the ceremonies. This aspect of Balinese life has caused a lot of tension. When we came to live here, I faintly hoped that the Balinese Hinduism might somehow inspire me in a spiritual way. Unfortunately, that has not materialized. Balinese Hinduism as it is practiced in my family-in-law, places little stress on religious understanding. For example, during ceremonies the sequence consists of preparing offerings, gathering in the temple, and pray together followed by the blessing of a family priest. Although I have not been raised in a Christian family, I have often been to Church with friends or family members who are Christian and occasionally felt uplifted by the reverend or pastor’s sermon. I missed that element in the Balinese ceremonies.

Another reason why I could not warm up to the religion that is my own according to my identity card, is the huge amount of time it absorbs and the relatively strict gender division of labor when it comes to all the tasks that have to be performed in the context of ceremonies. Women usually make the offerings for these ceremonies, which is very time-consuming. There was a period in the beginning when I tried to learn a bit about this. But lacking the religious conviction that all this is really necessary for our wellbeing, not to speak of the salvation of our soul, I felt as if the person who was trying was not really me. For that reason, I have given up trying. I felt relieved after I had taken that decision. This does not mean that I do not attend ceremonies, which would be ‘unthinkable’ anyway. Fortunately, I have come to enjoy these to some extent, as ceremonies are great social events providing an excellent opportunity to catch up with relatives. I also have come to appreciate the ritual way of the Balinese to deal with death. In particular, if the deceased is cremated right away, the family gathers for days for the preparations, which allows plenty time for overcoming grief.

Fortunately, my husband’s attitude is undemanding and understanding. He has even made an arrangement with his brothers and their wives a few years ago that for the ceremony held every seven months at the family temple in Klungkung, the offerings are made collectively instead of per family as used to be case before. Our contribution to the collective set of offerings, is limited to a particular item, which is ‘within my limit’. For the family the arrangement is also advantageous, because they have to spend less money and time on the offerings than before. Lately, my husband has drawn closer to his religion, praying every day for a short moment at the shrines in our yard. I assume that he thinks it is a pity that I do not share this with him, but probably has resigned to this situation as I have in other matters.

Of course, a difference in religious background (or in my case a secular ‘humanist’ background) does not rule out the possibility that basic values are shared. My husband and I have no different ideas about what a morally decent person is and are united in our opinion when someone crosses that line. My husband helps many people, (not only relatives!) in their troubles, helps young people with their education and if possible, gives or finds them a job. I admire him for that tremendously and try to support him to my best ability.”

How was raising a family together, coming from two different cultural backgrounds?

Sita: ‘The birth of our children was the most exhilarating experience we have shared together so far. We were so happy! Oka fought his way into the delivery room in both cases. The midwives in charge tried to keep him away, not being used to husbands wanting to be present when their child is born. Very touching was that an older brother of my husband and his eldest sister with her husband who had come especially from Bali were in the hospital when our first daughter was born. When his brother came to have a look at the baby, he confessed with tears in his eyes that he had been so afraid! They are still my favorite in-laws until today.

Cultural differences may lead to differences concerning the upbringing of children. But we have had no major disagreements on this so far. At the time, we decided not to send them to an international school in Bali, because we were unsure whether we would be able to pay the high school fees for both of them in the years to come.

Both of us were also of the opinion, that we would like them to become Indonesian children and feel part of Indonesia (and Bali), despite their mixed background. They now feel that they are Indonesian in the first place, which is fine with me. Telling is that their closest friends are Indonesian, not Eurasian or western. But inevitably, having a Dutch mother has influenced how they have turned out as well.

I have consistently used Dutch with them since they were little and until the age of ten have read Dutch children’s books to them every night before they went to bed. My involvement in women’s issues, often discussed with them when they were older, has made them perhaps somewhat more outspoken than the average Indonesian child. They are used to looking at problems from more than one perspective. The most important thing is, that we are sure they have no ‘identity problem’, they have ‘roots’. Where they will go from there, is up to them. Our eldest studies in the Netherlands now and feels quite happy there. Will she return? We do not know.

The most essential problem of a multicultural upbringing lies perhaps in the area of conflict. The few times a fight erupted between one of them during their teenage years and us, their assertiveness ran counter to their father’s ideas about parental respect. On these occasions, it has been difficult for me to find a balance between supporting my husband in his understandable grievance, while at the same time calling for restraint and, on the other hand, conveying to my daughter that she had stepped over the line in a way that made her see the point. As my approach sometimes earned me the reproach of my husband that I sided with our daughter, I used another approach when the girls were older, leaving them to fight out their differences with their father and trying to mend things later on. This works better, for them and for me also! Fortunately, emotional outbursts of this kind have been rare.

I cannot say this about the relationship between my husband and myself. Being both temperamental, but also because we had to cope with so many problems external to our relationship, we have fought a lot. My husband found and still finds our fights far more excruciating then I do. I have been brought up with the idea that having it all out and putting differences on the table, is a good thing leading to the solution of a problem and you can do that spontaneously, without paying much attention to being diplomatic. I have learned that this attitude is definitely counterproductive in the relationship with my husband. He clams up.

We ended up being a classical example of what is described in the famous American bestseller by Patricia Love: women talk, men walk (away).”

Cultural differences played a role as well. Unconsciously both of us used certain tones of voice, facial expressions and particular phrases engrained in our different ‘conflict cultures’, which definitely added to feelings of offence and hurt. Twice, I have consulted a psychiatrist (in Holland) how to overcome all this, which has been helpful. Older now – and a bit wiser I hope –, I have made a conscious shift to a more gentle approach, which gives far better results in sorting out certain problems with my husband. Still, I cannot always help myself and there we go again!’

Is it true that you chose to abandon your Dutch nationality, and now hold an Indonesian passport? Sita: ‘Nationality was a not a difficult dilemma for me. Compared to people marrying someone from their own country, mixed married couples often have to deal with bureaucracies and differing regulations to a far greater extent, which in the Indonesian case until recently used to be very discriminative against the foreign spouse. At first, there was no question of changing my nationality and all paperwork was taken care of, because I worked for the Dutch government during the first years in Indonesia. After that, I did not feel like changing my nationality as I wanted to be able to leave the country on the spur of the moment in case my mother would fall ill or another calamity would happen in my family. My mother passed away in 2000, so this reason for keeping my Dutch nationality fell away.

I started thinking seriously about changing my nationality, because there were several obvious advantages. No need to extend my residence permit anymore, always an expensive step because of the proverbial money that had to be paid under the table as well as a humiliating experience because Indonesian bureaucrats can be very rude to mixed married couples. As a foreign national it was very difficult to work officially and I was not allowed to ‘appear in public’, which I did. Becoming Indonesian would solve these problems. I was also terrified by the prospect that in case my husband passed away, I would have to sell the house within a year if I kept my Dutch passport. Moreover, we did not plan to move back to the Netherlands anyway. The only possible reason for this could be hell breaking loose in Indonesia. But I did not want to keep my Dutch nationality out of fear. One just has to have a little faith. All this probably sounds very rational, having nothing to do with feelings of being ‘Dutch’ or ‘Indonesian’.

I still feel Dutch and probably come across as Dutch in my manner. I have a terribly Dutch accent. But I am far more concerned about Indonesia than about the Netherlands.”

I read Indonesian papers, not Dutch papers. I write about Indonesia, I talk about Indonesia. It is not that I think Indonesia is such a wonderful country. In many aspects, it is a mess, and scoundrels abound from corrupt high officials to religious extremists. But Indonesia is an extremely interesting country, it faces huge challenges. Being part of that, in a modest way, is where I want to be (most of the time). So, in that respect I have become Indonesian. I did not become Indonesian for practical reasons only.

Once I had made the decision to change my nationality, I hoped everything would be arranged in the official timeframe. I ended up in a web of intrigue at the municipal court of justice, which handles applications for Indonesian nationality. I will spare you the details, but it was a tremendous source of tension. Close to a year after I had submitted all the necessary papers, the official in charge (was he really the one in charge? I still don’t know) returned the whole file to me saying he could not help me, meanwhile having pocketed several million rupiah for his ‘services’ which he did not return to me as well. Desperate I contacted a friend who is a lawyer in Jakarta for advice. She replied she would look into the matter. Two weeks later, a facsimile with the disposition of the Ministery of Justice rolled out of our fax machine at home. I called my friend and asked her: Do you have anything to do with this, Nur? Well, …. Yezz…, she answered slowly. At that moment, I knew I had made the right decision changing my nationality. It is not because the bureaucracy has to like me, but having people who want to help me here and think I am worth it.

I have not regretted my step for one moment. It indeed feels as if I have crossed a line: I am now on ‘this’ side, instead of somewhere in between. That has given me peace of mind. Later I was informed that the Dutch government changed the law, making it easier for foreign wives to get their citizenship back if they want to return to the Netherlands. I must admit: that gives a good feeling too.

Any advice for other cross-cultural couples?

Sita: ‘The first advice I would like to give people who intend to marry a partner from another culture is to be open about what one expects of a life together and, equally important, what one definitely does not wish to sacrifice or rejects. If this becomes clear after marriage, it is still legitimate to discuss this. Do not keep back. If things get rough between the two of you, it may help you to make a list of things, of not only what you do not like or feel bad about, but also of things that go well. It helps to keep your perspective clear and balanced. It helped me a lot to do this at one time, because after I had made that list, I realized that I had actually many things I should be grateful for. Count your blessings, is the motto.

As far as complaints go, you can try to figure out which issues you can deal with yourself. I found out that there were things I expected my husband to take care of, but he did not. I usually knew the reason why. Once I realized that I could just as well take the matter into my own hands, the list became shorter. If the list of positive points is far shorter than the negative ones, there is always the option of seeking help of others. If you have to seek help on your own, because your partner does not feel like it, do not make a problem of it, but communicate back to him or her, what you have learned on a suitable occasion or ask someone trusted by your partner to mediate. Be patient.

In particular, if your marriage is blessed with children, you are in my view obliged to them to exhaust all possible means before breaking up. They will lose so much more when their parents separate than when their parents live in the same country. Whomever they will follow, the ensuing physical distance will often have dire consequence, such as them losing contact, with not only one parent, but the entire side of the partner’s family, as well as an undeniable part of their own identity. That is a very heavy toll.

I also recommend the foreign spouse to keep a private saving account in his or her homeland. He or she will probably feel more secure when having the means to return at any time, whether it will ever be used or not is not the issue. If one of the partners possesses very valuable assets, it might be wise to keep part or all of this apart by way of a nuptial agreement and one common and two separate bank accounts can also be useful. This may all sound unsympathetic and can be interpreted as a token of distrust of your partner. But in my view it is a token of love and respect to give your partner a certain measure of economic independence, even if that partner does not bring in much. It is also wise for a mixed married couple not to put all their eggs in the same basket in view of the sad fact that so many mixed marriages break down. It helps to come to a reasonable settlement in the case of divorce. Over time, when the marriage has become stable, you may feel that the need for these measures becomes less.

My last piece of advice is not to enforce any decision on your partner. If you really want to have your way, persuasion is the only acceptable option. Talk and talk again. If in the end, your partner still does not agree with you, accept that. A decision executed without a partner’s approval will not be forgotten and may lead to a permanent grudge. This advice is of course not just relevant for mixed married couples. But because they have often more and more difficult decisions to make than other couples, biding by this principle is even more important.”

Any last words? Sita: ‘I like to end on a positive note. The most exciting aspect of our relationship is the enormous variety of people that are part of our life. The large extended Brahmana family of my husband, slightly highbrow, has drawn us into the hubbub of Balinese life, with all its life cycle and other ceremonies, mutual assistance obligations, and – of course – family troubles, feuds and gossip. There is always ‘something going on’, ‘never a dull moment’.

Like in any family, there are likeable and less likeable relatives, no different from where I come from. The scale, however, is different. My husband’s enterprise employs Balinese as well as Javanese people. We go to their weddings and my husband and I see to it that they get medical care when needed. They confide in us, which makes us feel valued. When they come back from their village, they often drop gifts of vegetables, fruit or traditional snacks at our place. That is nice. I like that. I have the privilege of having many friends and acquaintances from Bali and elsewhere in Indonesia who work at the university or for an NGO, who drop by for a ‘discussion’ or I go to their place or office. Foreigners often pass by as well. Nearly every year, relatives from Holland stay with us for days or sometimes weeks, in particular during the summer months. Friends and colleagues of mine often stay over for lunch or dinner, which I appreciate very much. My husband has many foreign clients of Dutch but also other nationalities, who come from many different walks of life. With some of them a friendship has developed.

This picture would not be complete without mentioning our assistants in our household, at present Kadek, I Luh and Komang. They are an amiable lot, who tell me all kind of stories of their families in the village and make it possible for me to devote a considerable part of my time to other activities than household chores (like joining this series). I am sure, that we would never had such a wide and varied social network if we had stayed in the Netherlands.

The consequence of this is that we have to juggle with our time and cleverly divide our attention. In my opinion, we are good at that. It also gives us a measure of satisfaction beyond the relationship we have together and with our children, which of course always comes first.’

Latitudes: In the Mix In this series we talked to people with a mixed Asian background. Have these colorful roots entangled them? Confused them? In what way has their heritage formed their identity, how do they look at the world & how does the world looks at them? In the next weeks we will re-publish this series, because the articles and interviews were very well read at Latitudes.nu. And because it's so nice to see all these couples again.