By: Anthony Sutton, published in Jakarta Expat edition 53

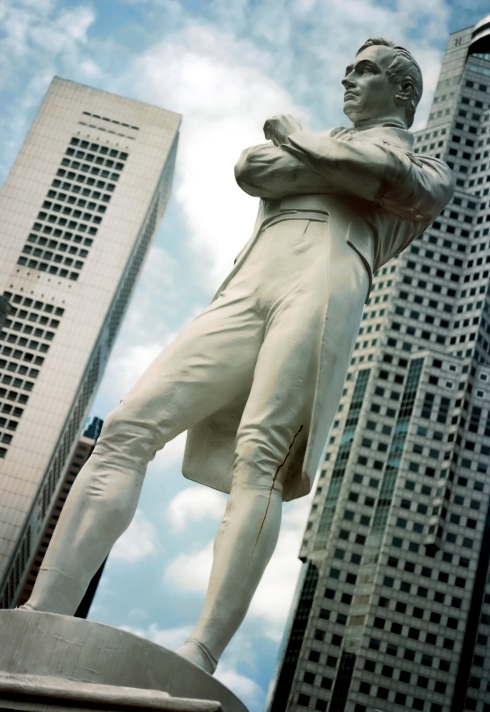

Anyone with but the flimsiest knowledge of Indonesia will know the pivotal role Yogyakarta has played. In culture, in rebellion, in battling invaders the Kraton has been at the heart of the Javanese story. And Stamford Raffles is a man forever linked with Singapore despite the fact he spent much longer on Java than he did on the fledgling island state. He also spent five years on Penang and from there he cast envious glances at the long narrow island that lay beneath the equator, seeing it as vital to British interests in the East.

He formulated a plan to bring the island under British control, kicking out the French in the process and sailed to Calcutta to convince the great and good, his paymasters there. His enthusiasm got them on board and in 1810 he sailed for Melaka to assemble the forces needed for such an operation as well as develop the human intelligence vital to the success of the mission. That he spoke the language and was sympathetic to the locals was in his favour and for several months he intrigued from the historic port on the Malay peninsular.

Raffles in Java

When the conditions were deemed correct, both at sea and in Java, the force set sail, heading south past the island of Singapore and across to the great isle of Borneo before turning south and heading for a spot just west of the port of Batavia. Here, the British invaded and pushed the French south to the great castle of Cornelius which was besieged before finally falling.

Now it was time to spread out across the island, develop the contacts Raffles had developed from afar but in Yogyakarta the welcome was not so warm. He had been warmly greeted in Solo, but things were not going well further south so it was with some trepidation that he entered the Kraton with a mere 900 troops as support. He gained entrance to the Sultan’s inner sanctum where some hundreds of armed men looked on with ill-disguised loathing at these new intruders.

There was an issue over the seating arrangement that would have left Raffles looking inferior to the Sultan and not as the leader of government. Things got heated for a while and daggers were drawn as the mob moved in, the Sultan sneered at the visitors. Had the Sultan signaled the attack, there was no way the visitors would have succeeded, so outnumbered were they but say what you like about Raffles, he had guts. He insisted the chairs be rearranged, inferring it was all a misunderstanding, but showing confidence and strength and the Sultan acquiesced. An agreement was reached as with the other sultans on the island, extending all privileges to the British as had been extended to the Dutch and the French previously.

No one was convinced as to the relevance of the treaty. The British widely believed the Sultan would renege as soon as the opportunity arose and within months was co-opting the Sultan of Solo and running around killing some local chiefs and building up his defences.

The British returned with another small force to bring matters to a head. The Sultan spurned messengers seeking he negotiate so the British took occupation of a fort opposite the Kraton that had been developed by the Dutch. As the British forces approached Yogyakarta, they were attacked by rock throwing natives but had little trouble encamping.

Facing the invaders was a force of some 40,000 troops well armed as well as a large number of cannon. The Sultan, confident such a small force was no match for his larger forces, offered them an unconditional surrender that was rejected out of hand. The British attacked, feinting at the main north gate while a larger force had crept through the surrounding kampongs unnoticed and attacked the northeast section of the walled compound. It took three hours to take the Kraton and the Sultan was expelled to the Island of Bangka, recently handed to the British and renamed ‘Duke of York Island’. His brother was named Sultan and the Palace was moved to Pakualaman Kraton, a little to the east.

Raffles returned to Batavia and Bogor to earn his salary that was for administering the island to the greater good of his employers, The East India Company. But one gets the impression that Raffles was never happier than when he was out getting his feet dirty exploring and recoding the history and fauna of a place and that dealing with autocrats was a mind numbing distraction for him. He gathered about him a team of like-minded fellows and had them running round Java learning as much as possible about the place and it wasn’t to be long before he heard something that intrigued him greatly.

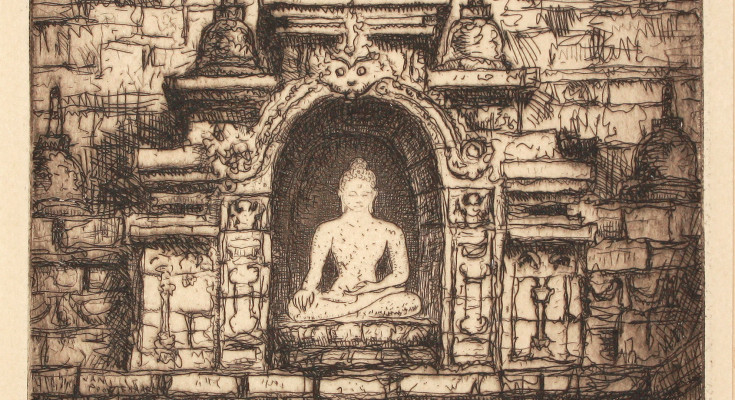

Buried Borobudur as The Hill of Statues

It is likely he was already aware of Prambanan, sitting then as now, by the main Solo – Yogyakarta road but what is unclear was when he first heard of the Hill of Statues. When he did hear of the presence of some monument of great antiquity, he approached a Dutchman, Cornelius, and asked him to head down there and take a look. Given the travel time involved, Raffles would have head to content himself with the day-to-day tedium of running Java, waiting for news from his envoy. At the time, he cannot have held out great hopes, after all, he would have often been told of some great building only to find little of substance. But he made a wise choice in sending Cornelius, a man familiar with the region and a man familiar with Prambanan.

He was excited when he first heard from the Dutchman, but could not get away from the office. In November 1814, his wife Olivia died. Early the following year, his patron who had backed his mission to Java, Lord Minto, died. Raffles, never particularly strong in his own constitution responded in the only way he knew how. He climbed Gunung Gede, south of Batavia. He left Bogor on 26 April, 1815 and first set eyes on the Hill of Statues on 18 May, 1815.

At that time Borobodor was covered in undergrowth and statues of 504 Buddha’s laid scattered in the secondary jungle that had reclaimed the area. It supposedly took 200 men more than two weeks to clear away the scrub and with each branch hacked away a small piece of the whole was revealed. Raffles and his crew would have gazed on in amazement at the scope of what was laid before them. The ‘extent and grandeur’ mixed with the ‘beauty, richness and correctness of the sculpture took his breath away and left him with a myriad of questions. Who? What? When? Why?

While Raffles was taking in the monumental vista before him, events were moving rapidly on the battlefields of Europe. A rejuvenated French army was defeated at the Battle of Waterloo and as part of the peace Java was returned to the Dutch. Raffles was out of a job. Borobodor was ignored when the Dutch returned and slowly the jungle returned. Not until the French ‘discovered’ Angkor Wat in Cambodia did interest turn again to the Hill of Statues. And today, as one million visitors a year tread the tiers of this ancient monument in the footsteps of Raffles, the same questions are being asked.