By Dina Indrasafitri

Plenty of women work and take public transport in Jakarta. Statistically, much of violence towards women happen in the domestic sphere, but apparently many cases also occur in the public sphere. Hundreds are rising to demand women’s right to be safe on the road in a city that has been labeled one of the most dangerous in the world

Arie, a thirtysomething housewife, felt a stranger touching her indecently when she got off an agkot (public minivan) in South Jakarta, Indonesia, to go home last week. Triggered by anger and egged on by the screams of another passenger, she hit her assaulter’s face and yanked him out of the minivan, thus causing him to suffer facial injuries. While friends applaud her on social media for her reaction, she admitted that she feels lucky to have escaped any retaliation from her attacker.

‘Public transport is supposed to give a sense of safety for its users’

Efi Sri Handayani raises her fist for the One Billion Rising movement in Indonesia.

The area was close to a district court, and many onlookers, including several security officers, soon gathered to restrain both her and her attacker. “I did think to myself, ‘Am I doing something stupid?,” She said after recounting her story. A few others had indeed been less fortunate. Indonesian media has reported several particularly grisly cases in which female users of public transport in Jakarta was sexually assaulted and even murdered. One example is the robbery, murder, and rape of university student Livia Soelistio in 2011. She was also taking a public minivan. Last year, a number of officers from the Transjakarta transport facility in Jakarta sexually assaulted a passenger who fainted due to an asthma attack.

Existing statistics don’t bode well for the city either. An Economist Intelligence Unit report ranks Jakarta last in the Safe Cities Index 2015, although the report states that ‘ a city coming number 50 in the list does not make it the most perilous place in the world’. Meanwhile, a poll by Thomson Reuters Foundation ranks it as having the fifth most dangerous transportation system for women, among 16 of the world’s biggest cities. Prompted by cases involving sexual harassment in public transport, participants in Indonesia’s One Billion Rising (OBR) Movement are demanding safety for women in the transport facilities and streets of Jakarta.

The One Billion Rising movement was founded by American activist Eve Ensler. It aims to end violence against women, taking its name from a statistic saying that one in three women will be raped or beaten during her lifetime. This year, the global movement calls for a rise ‘for revolution’, but its Indonesian counterparts decided to take on what they see as a more appropriate theme. “At the end of 2012, we got so many reports of sexual harassment in public transport…” Efi Sri Handayani, an OBR participant said, during the movement’s ‘rising’ event last Valentine’s day in Taman Ismail Marzuki art center, where participants gather to dance and campaign their cause.

Participants of the One Billion Rising movement rehearse their dance moves before the ‘rising’ event last Valentine’s Day in Jakarta

“Plenty of women work and take public transport. Statistically, much of violence towards women happen in the domestic sphere, but apparently many cases also occur in the public sphere,” she said. “Public transport is supposed to give a sense of safety for its users.”

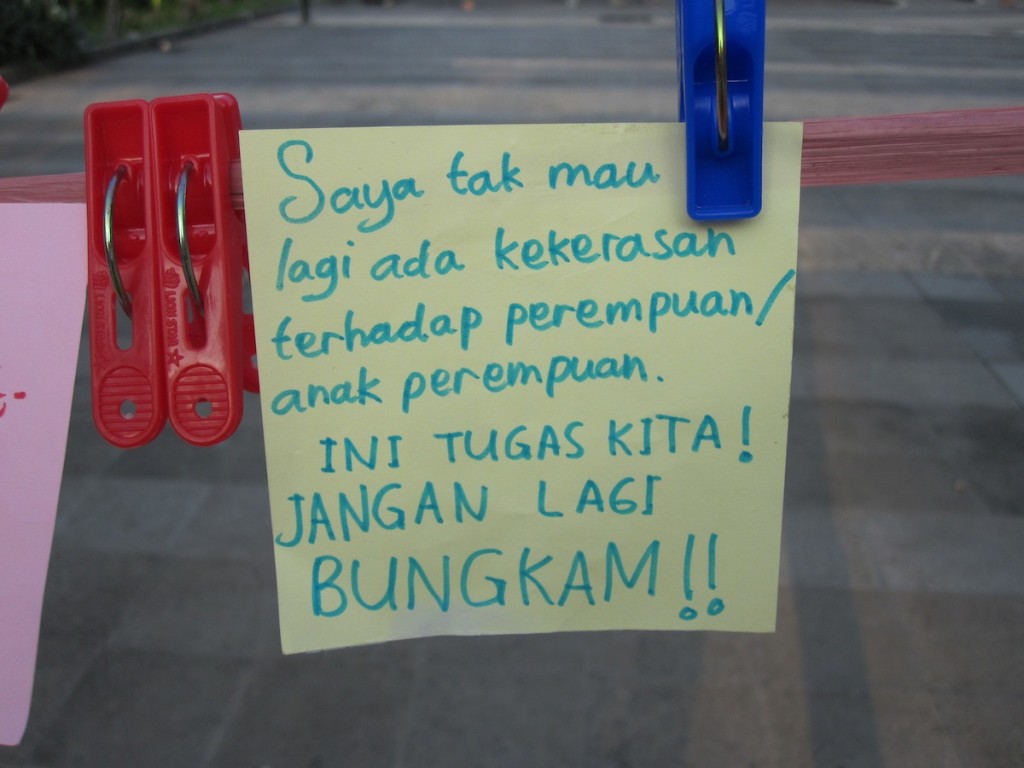

A message from supporters of the One Billion Rising movement in Jakarta, saying ‘I don’t want any more violence towards women/girls, It is our duty! Do not keep silent!’

Dhyta Caturani, another participant, says that the government’s moves to address the issue, such as providing women-only carriages in trains, are inadequate. “[women’s only carriages] is not a solution because when we talk about safety for women in public spaces, it should not be limited within those carriages,” she said. “It has to be holistic. We have to change the community’s mindset, about women having the rights to safety and be free from violence.”

Despite gruesome cases and woeful statistics, Dhyta said there have been some improvements in the issue of the safety of women in Indonesia. “One of the successes of the women’s movement is the increasing awareness of the community, that [violence against women] is not something that is allowed. We can see more women reporting [incidents of violence against them],” She said.

A report by the National Commission Against Violence Towards Women shows constant increase in the number of victims of violence against women from 2010 to 2013. “It may be the case that there are more cases of violence, but another way to see it is that more victims are willing to report it,” Dhyta says. Governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama and the police have also reportedly pledged to boost the safety of the city through installing CCTVs and through usage of other technology-based measures.