By: Farid Rakun

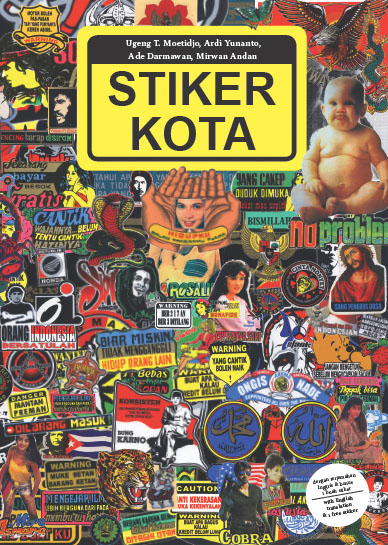

Cover of the book Stiker Kota

Cover of the book Stiker Kota

To talk about contemporary graphic design in Indonesia, we have to acknowledge the ubiquity of stiker kota, or city stickers. Stiker Kota are small (usually less than 15 centimetres wide), cheap, popular stickers that circulate widely through urban networks. Designers are generally anonymous and work by responding to the popularity of their designs (judged by sales and their appearance on urban surfaces) as well as trends in popular culture. Jakarta-based, artist-run initiative ruangrupa considers stiker kota a visually-rich social phenomena and has been researching and archiving them since 2001.

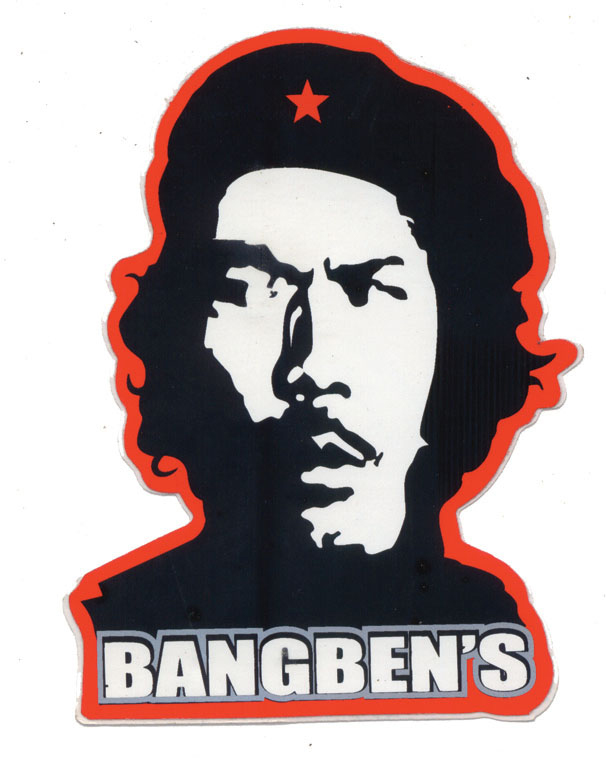

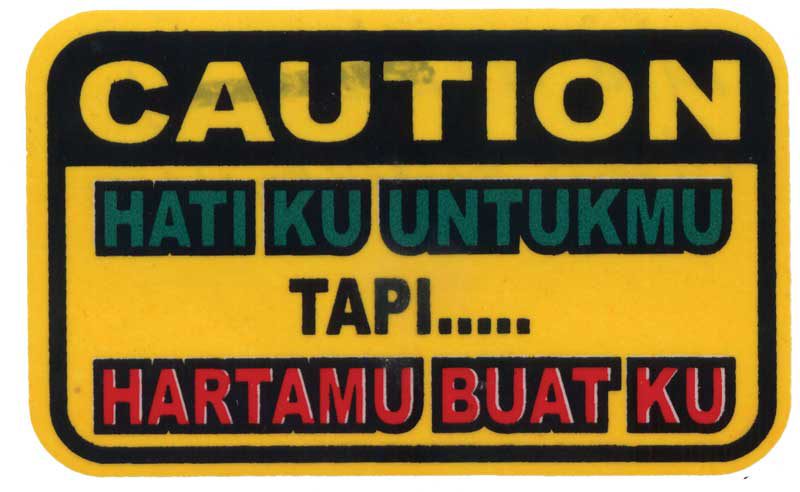

Stiker Kota have played an important role in mediating public opinion in Indonesia. Through the making-distributing-choosing-buying-pasting-consuming of the stickers, tensions can be raised and silently resolved between competing forces. It is on these surfaces that moralistic views and their liberal counterparts are provided an early and even battleground. Humour goes head-to-head with religiosity, neither ever clearly emerging as a winner. Here, Qur’anic calligraphy can sit next to a portrait of Jesus Christ, who is looking down to ‘Chewe Guepara’ (freely translated as ‘my girl is nasty’), a textual and visual pun of Che Guevara. All done in peace, without causing a rumpus: bebas tapi sopan (liberal but proper).

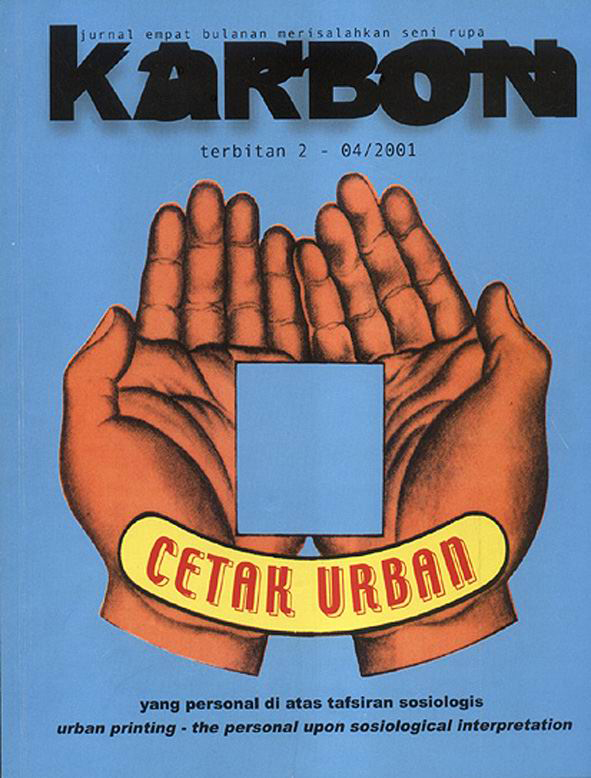

Cover of the 2nd volume of Karbon journal

Cover of the 2nd volume of Karbon journal

These stickers were mainly produced in small villages, with the biggest supplier, AMP Prod, located in Pakisaji, near Malang in East Java. At least 70 per cent of stiker kota available in Jakarta, Bandung, Semarang, Surabaya, Malang, and Blitar were printed by AMP, whose history tells a story of urbanisation in Indonesia. First, with the change from agrarian to industrial society, the founder of AMP, Kusnadi, in 1974 stopped working as a sugarcane laborer, and worked as a courier for a company owned by Koh Beng, learning sticker production on the side. In 1977, with his wife Pujowati and her brother, Haryanto, Kusnadi founded his own company and named it AMP (Adi Mas Putra – little brother, big brother and son).

As with every commercial practice, the belief in growth and labor efficiency was paramount. Thanks to mechanisation, AMP slashed their number of workers from 150 at the end of the 1980s, to only 75 in 2008, while steadily increasing their productivity. Until 1998, the scale of production only allowed distribution to Malang, Surabaya and Blitar. During the 1997-98 recession, when a lot of the competition went bankrupt, AMP took on a lot of new clients making it the biggest player in the business nation-wide. AMP’s story demonstrates the ubiquitous effects of urbanisation. Hundreds of kilometres away from urban centres, villages also transform their industry, producing and linking to the communication systems of urbanites.

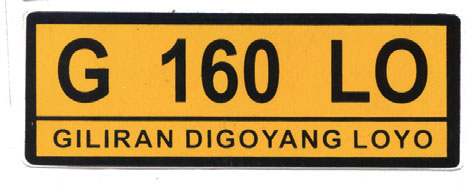

GIliran diGOyang LOyo (impotent when rocky)

GIliran diGOyang LOyo (impotent when rocky)

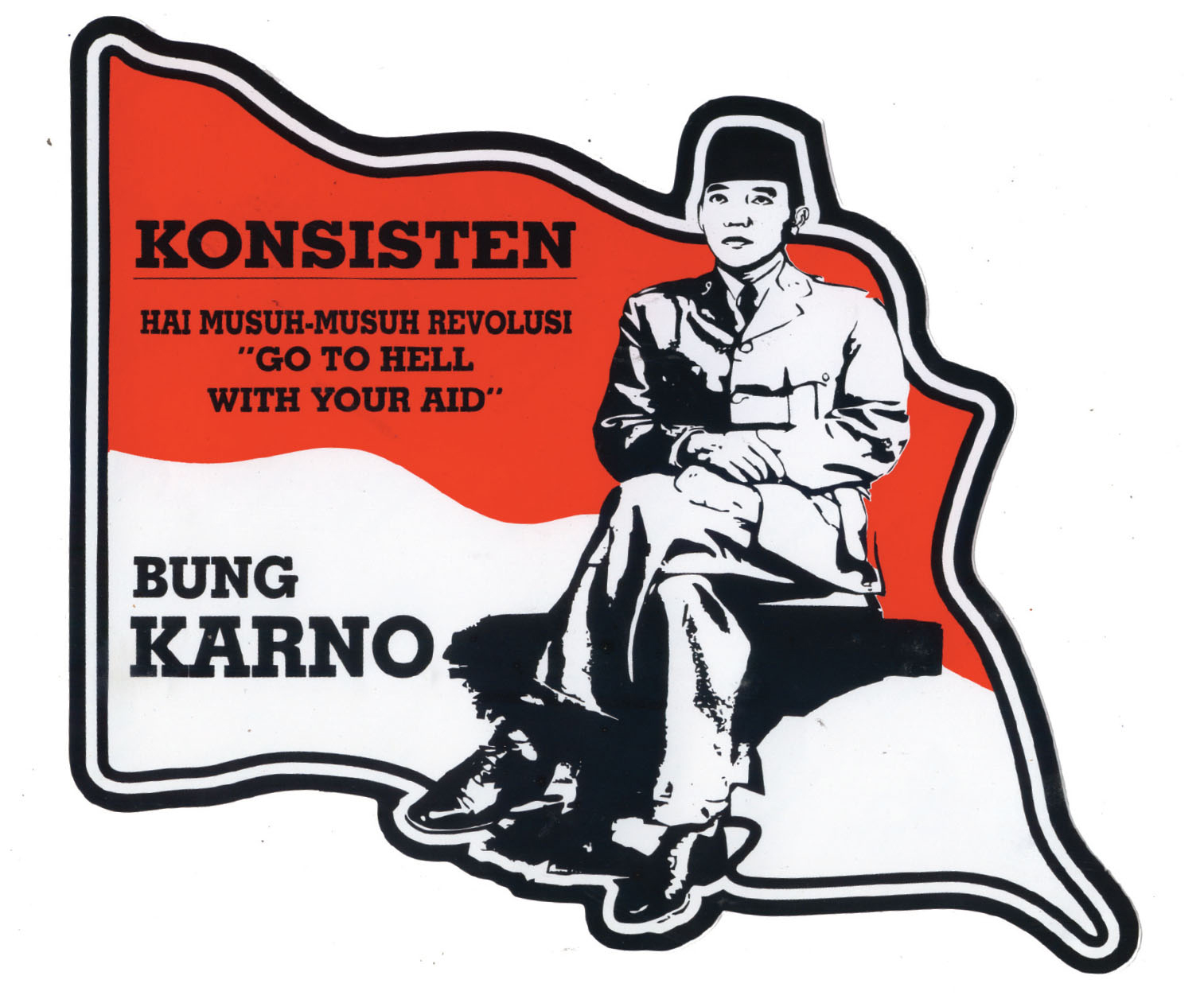

Consistent. Enemies of revolution “go to hell with your aid”. Bung Karno

Consistent. Enemies of revolution “go to hell with your aid”. Bung Karno

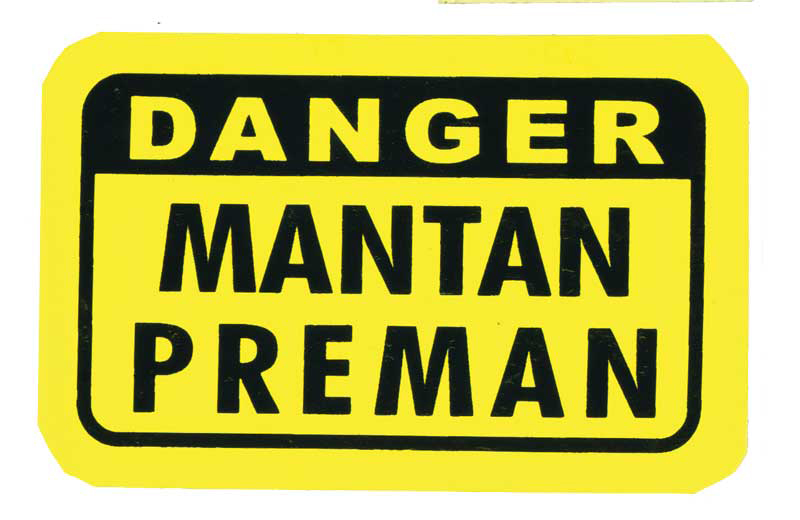

Additionally, we found in AMP’s history of product diversification a story analogous to the history of freedom of expression in Indonesia. The birth of the business was made possible through the production of religious stickers, but it then diversified, starting with the classic popular idioms such as ‘Sekarang bayar besok gratis’ (‘pay now, free tomorrow’). What followed was supply for the demands of an image-crazed society: sexy girls—scanned directly from calendars—were printed on the same presses as the verses from the Qur’an. The final culmination was the warning sticker series – which allowed a seamless juxtaposition of religious and popular culture with slogans such as ‘Utamakan Sholat’ (honour prayers) with ‘Mantan Preman’ (ex-gangster).

Danger. Ex-gangster

Danger. Ex-gangster

Warning. Satanic face, (sticky) rice package. The most common form of the Warning series, depicting a subtle sexual pun

Warning. Satanic face, (sticky) rice package. The most common form of the Warning series, depicting a subtle sexual pun

Che Guevara depicted as Benyamin Sueb, a legendary comedian from Jakarta

Che Guevara depicted as Benyamin Sueb, a legendary comedian from Jakarta

In recent years as online social media, personal publishing platforms and digital printing have emerged, stiker kota has been fading in the urban landscape. Instead of attaching a humorous image-text design to their motorcycle bumpers the trend is towards tweets and touchscreens. Stiker kota are becoming obsolete, and in that process, the urban surfaces that used to provide territory for shared entertainment are sterilised. As we reminisce over the design of the stickers, tagging #stikerkota on our smartphones, we also remember a time when one meme could literally be stuck over another in the mess of urban surfaces.

Stiker kota translates directly to ‘urban stickers’. A book of the same title was published in 2008, by ruangrupa (Ugeng T. Moetidjo, Ardi Yunanto, Ade Darmawan, and Mirwan Andan). It was a continuation of similar efforts, previously published in 2001 as the second volume of Karbon journal, entitled Cetak Urban: Yang Personal di Atas Tafsiran Sosiologis (Urban Printing: The Personal Upon Sociological Interpretation) for which Ade Darmawan, Hafiz, and Ronny Agustinus acted as editors. More recently, Ardi Yunanto revisited this subject in Mengenal, atau Mengenang, Stiker Kota (Knowing, or Remembering, Stiker Kota) for Jakarta Biennale 13: SIASAT (for which Ade Darmawan served as a curator). This essay is an attempt to briefly reintroduce these initiatives and their findings for nonIndonesian readers.

My girl is nasty. Collage remixing Che Guevara portrait

My girl is nasty. Collage remixing Che Guevara portrait

Caution. My heart is for you but… your wealth is mine

Caution. My heart is for you but… your wealth is mine

farid rakun is an artist, writer, editor, teacher and instigator based in Jakarta. Trained as an architect, he currently serves as editor and researcher for the artists’ initiative ruangrupa, while teaching full-time at the University of Indonesia.