An interview with Andreas Siagian

By: Rebecca Conroy

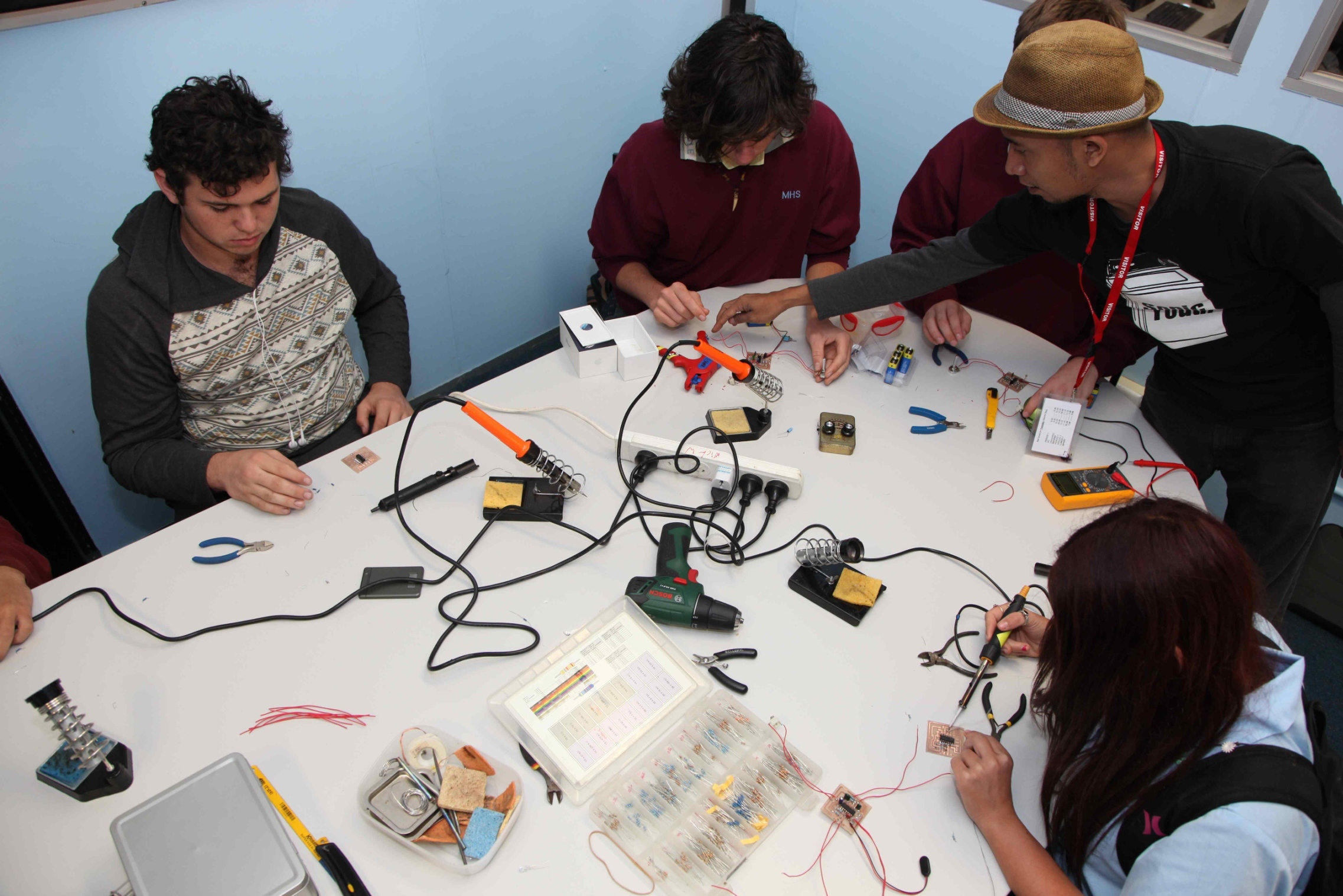

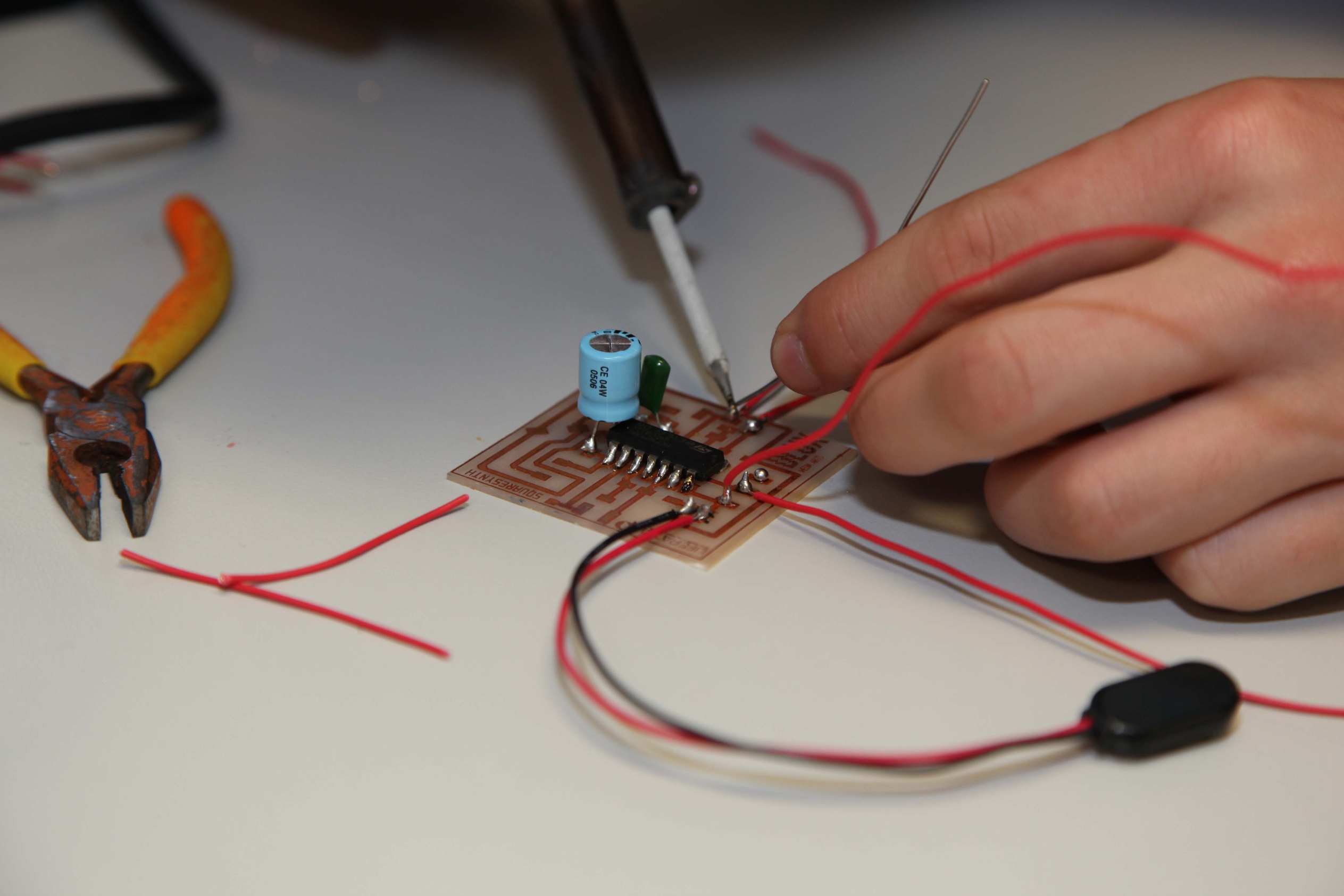

Kempsey Residency workshop with Melville High School – Yenny Huber/dLux Media Arts

Kempsey Residency workshop with Melville High School – Yenny Huber/dLux Media Arts

Andreas Siagian is a cross-disciplinary artist with an engineering background focusing on creative communities, alternative education, DIY (Do it Yourself) and DIWO (Do It With Others) culture and interdisciplinary collaboration in art, design, science and technology. He was recently in Australia as the international visiting artist for dLux Media Arts dLab program. His collective, Lifepatch, is based in Yogyakarta and uses social design methods to encourage experimental thinking and practice amongst the community.

How did you get involved in the DIY art and science community in Indonesia?

My background is in Civil Engineering. I completed my undergraduate study (in Indonesia) between 1998 and 2005. During that time, there was major change in Indonesia politically, because it was the end of the regime of Suharto. I think for my generation, we were quite lucky to be growing up and witnessing these changes. Of course, it also impacted many layers of society and one of the biggest changes was to freedom of speech and freedom to express yourself. At that time, the art scene was impacted by Suharto because he was the enemy of the art movement, of politically engaged art practices. At that time, while I was at university there was a new culture emerging. I got involved in the electronic music scene, helping to organise electronic music gigs and events. One thing in particular that made me really change was an AV programming workshop by a collective, RYbN from France (http://rybn.org). They were the reason why I was interested to jump into the art world.

What have been some of the changes in the post-reformasi era?

In the past ten years, most of the community were able to talk freely or make an artistic statement about what’s going on, what’s wrong with society and discuss political policies. Even so, since 2004, most of the intellectuals, 30 per cent, don’t vote for the presidency. They’re pessimistic about the failed realisation of many of the changes promised after 1998. But since the recent presidential election, many artists are once again seeing hope for the new leader. The use of social media in that sense was very much a part of helping them to state their support for Jokowi. This did not happen before 1998. Only the radical artist groups could really state their opposition to Suharto, like Taring Padi, for example. But I think there are still very few artistic groups that have a strong involvement in political activity the way Taring Padi did in 1998. Now it’s more diverse. Community engagement is more about critiquing education policy in Indonesia.

Can you talk about Lifepatch, your organisation?

It’s been two years since I co-founded Lifepatch. I think there are limited options for young people in Indonesia looking to expand their knowledge. What is really ridiculous is that while there are possibilities that can come with the internet, the curriculum changes required for the formal education system are not up to speed. That is why the main focus of Lifepatch is on sharing knowledge with the people. Until now, there were no formal education options for learning about new media – there is no school for that. At Lifepatch, we question global technologies and science – the trends. We realised that Indonesia lost many traditional sciences during colonisation. We try to bring this specific issue of traditional science into our practices because we think it is very important and very interesting.

Can you give some examples of what those traditional sciences are and talk about your specific approach to disseminating that knowledge?

Alternative education forms and social design can really help us to innovate because there are limited options available in formal execution. Ideally, both groups should work together to address this issue. For example, the wine project starts with the question, ‘what are the local alcohol products from Indonesia?’ We discovered that there is no local beer. Bir Bintang is actually Heineken and Anker is from San Miguel. So we question what is this beer: it is made from a plant that is not naturally grown in Indonesia. Meanwhile, there are plenty of informal alcohol products that are made in Indonesia such as Ciu, Lapen, Arak, Tuak et cetera. Because of the suppression of alcohol cultures through government policy, people are inhibited from experimenting and developing a product that is drinkable – where people drink it because it’s good, not because they want to get drunk. We started that project in 2010 when the government introduced a new policy, increasing the alcohol tax to 40 per cent. We started by asking the scientists from Microbiology at Gadjah Mada University (UGM) to help us understand fermentation and we commenced experimentation by making wine from tropical fruits. We experimented with 30 different fruits and tried to finesse the taste so that it tasted good and was safe and hygienic for the people. By understanding this process, we could creatively distribute the knowledge to the people. We conducted workshops and people were asked to bring their own water bottle, hose and candle to start their own fermentation project.

Kempsey Residency workshop with Melville High School – Yenny Huber/dLux Media Arts

Kempsey Residency workshop with Melville High School – Yenny Huber/dLux Media Arts

What is the future vision for Lifepatch?

We want to continue delivering and organising small-scale workshops. We believe that small-scale and continuous is better than large-scale and one-off. I think this is more effective for our social practices in the community. Our tagline is ‘citizen initiative’ because our field is both art and science, and we really depend on the collaboration between people who are involved in both these practices. If we call it an art initiative, then scientists don’t feel they have a space in that. We try to make it neutral for people from different backgrounds.

Who else do you work with?

We work in Yogyakarta. Recently, we collaborated with Kedai Kebun Forum, a local space, to organise Hackteria lab with Hyphen, Otakatik, Permablitz, Teapot experience, and many artists. We also worked with ruangrupa in Jakarta and we recently established a network with Jatiwangi art factory. WAFT-LAB has been our collaborator for a while. Internationally, we are part of Hackteria, an international network that was started by Marc Dusseiller and others. They have been coming to Indonesia every year which has been really important for the collaboration. Their practices have significant use in the context of Asian communities. Each time, we try to develop a model for the workshop that can be easily distributed to the people. We recently finished Hackteria lab 2014, and held a two-week lab and residency for all the artists and scientists. We connected this with local communities who also worked with us, such as Green Tech Community, microbiology UGM, Otakatik. We work to connect them so that they can establish their own international collaboration.

What is the role of DIY and DIWO in Indonesia?

The truth is that DIY has been an established practice in Indonesia for centuries because the government never worked for us (laughs). So we have this mentality, this sense of community that emerged from having to rely on our own resources to do anything. The distribution of knowledge should work with this DIY mentality, which has for a long time existed in Indonesia. When I hear people talking about open source hardware and software… in Indonesia, it doesn’t work like that. Like for us, for Arduino (an open source hardware that you can program) will cost Rp.300,000 (A$35)—that’s a lot for an Indonesian—you can buy 30 meals with that amount of money. Indonesia doesn’t operate like that. For example, if we want software, we can go to a CD rental shop, hand over our ID card and we can get a CD full of Microsoft software. So this hardcore attitude that you have to be open source, in reality we don’t work like that. We work with professors that are using Windows and so we have to work with that. We can’t say that you have to work with this open source Linux. This mentality can only grow with education. There is very little distribution of this knowledge in Indonesia, compared to the global movements and only alternative education practices can deliver this knowledge. That is why DIY and DIWO have to come with an awareness of sharing of knowledge and education to the society so that they can see that there is an alternative to what is made available by Bill Gates. At the moment, we just offer an alternative solution. But in the end, it is the community that must decide.

Rebecca Conroy is a writer and arts practitioner working across site, community engagement, and interventions through artist led activity. She completed her PhD in 2006 researching Oppositional Performance Practice in contemporary Indonesia, where she spent her ‘youth’. www.bekconroy.com.