The ‘Indische’ diaspora

A short history on migration and integration of Indo-Dutch and Indo-Americans 1950-2020. Similarities and differences.

(Lecture 12 Sep. 2023 University of California Berkeley)

By Peter van Riel

Indo-Europeans originated from intermarriage between European men and Indonesian women. Since and even before the VOC (17th century United East Indies Company, one would call it a multinational now), white European men came to the East for trade. However, no women were allowed. They therefore started relationships with local women, often with children as result. In studies they are labeled Indo-Europeans. They did not form a socially homogeneous group in colonial society. There were differences in social position, level of prosperity, religion and lifestyle. A considerable part of the Indo-Europeans consisted of the so-called ‘little bung’. One can translate this into ‘little brother’. They were mostly low-educated and low-paid and often lived in kampongs (poor neighborhoods) around cities. Within this group, the indication ‘Indo’ was used as a common designation for each other. But also as a classification. In newspapers, scientific studies, speeches, and within the community the word Indo soon stood for people of lower origin and low social position. The Indo was a bit looked down upon. This was accompanied by ugly stereotypes. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, the word Indo increasingly came to stand for all the negative qualities of the ethnic mixed. Essentially it was all about color that determined social acceptance by the white Europeans.The socially marginal position of this group was further reinforced by increasing poverty around 1900. The effect of this negative appreciation and emotional value, would last until after the end of the Dutch East Indies, within and outside the community.

Remark:

In this article I prefer to use the word Indisch instead of ‘Indo’, or even better: Indo-Dutch (litt: Indische Nederlander) or Indo-European. I am aware of the discussion on this subject, here and in the Netherlands. The word Indo still is used in the inner world, but has a somewhat negative connotation outside. I think Indisch or Indo-Dutch/European is more neutral. I will use them all three in this lecture. Although Jeroen might agree that the word Indisch in Flemisch means Indian. It’s a bit confusing.

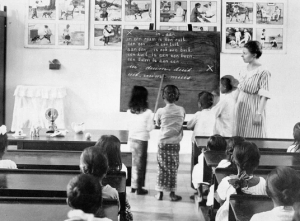

Primary school colonial times

World War II

In the 1920ties and 30ties ethnicity (skin color) had started to play a more important role due to the growing group white Dutch women that came to the colony. A side effect was that Indo-Europeans, in their effort to be on an equal footing with the Dutch, judged and treated each other also according to skin color. It happened within families that a lighter colored brother or sister was appreciated more and given better chances than the ones with a darker skin.Tragically, at the beginning of the Japanese occupation of the Dutch East Indies march 1942 (3 months after Pearl Harbor) many Indo-Europeans wanted to introduce themselves as Indonesian in order to stay out of the internment camps. The Japanese determined to what extent they were European or Asian based on their descent. Indo-Dutch believed the browner their skin the greater the chance of staying outside the camp. But, again tragically, many would lead a miserable life outside the camps. And that didn’t change after World War II, it even got worse. The end of the Second World War did not come at the same time for everyone. For the Dutch in Europe, the Second World War was officially over beginning of May, 1945. For the inhabitants of the Dutch East Indies, the war did not end until August 15, 1945. After the liberation of the Japanese a very chaotic period followed. Dutch, Indo-Europeans, and other minority groups had to fear for their lives. All kinds of local armed groups started to terrorize, abuse and murder citizens that were associated with the colonial elite. A civil war was feared and the Dutch government sent troops to restore power. My father was one of them. The decolonization war lasted for more than 4 years, followed by forced evacuation of thousands of Indo-Dutch inhabitants to the Netherlands. This whole process continued far into the 1960s. For many The Netherlands was a strange country, although officially their homeland.

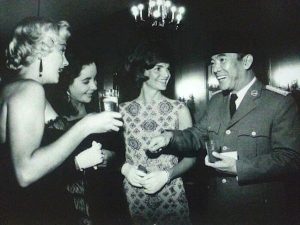

Sukarno visits the USA

Waves of migration

For the traumatized the war was never really over. It also later influenced the atmosphere and relationships within Indo-Dutch families, in some cases for generations. Finally roughly 300,000 Dutch citizens came to the Netherlands, including full blood Europeans, Indo-Europeans and Moluccans. In 1947 Pelita was founded to support the Indo-Dutch refugees that arrived. This great migration came in different waves: The first wave took place between 1945-1949 and consisted of evacuees, sick people, former internees and forced labourers. Mostly white Europeans. In the years 1950-1952 the migrants mainly consisted of white Europeans and Indo-Europeans – often civil servants – for whom there was no place left in the new Indonesian republic. Followed by those who did not want to become Indonesian citizens and thus lost their jobs and sometimes even their homes. The end of the fifties a huge group of ‘spijtoptanten’ departed. They initially opted for the Indonesian nationality. But regretted (spijt = regret) that choice due to a lack of prospects. Or sometimes because of harsh discrimination. The nationalization of Dutch companies and the issue of New Guinea (the last remaining colony in Indonesia) also played a role. The living climate worsened day by day. Not all left. The Indo-Dutch that stayed behind in Indonesia were unable to show a passport or prove their Dutch origin. They had no Dutch friends of relatives and stayed behind. Their number is estimated at over a million. They mostly live in poverty now. According to the Netherlands Demographic Institute, the number of 1st, 2nd and 3rd generation Indo-Dutch people now is approximately 1.2 million (of a total of 18 million). According to policymakers, the assimilation of the Indo-Dutch is considered as an example of successful integration of an ethnic minority. However many Indo-Dutch won’t agree. They experienced undervaluation and discrimination. Sometimes even until today. The ones that couldn’t adapt to the Dutch climate and living left for another destination. To the US and Canada, some of them even Australia.

Embarking ship with Indo migrants

California dreaming

The vast majority of Indo-Dutch immigrants live in southern California. Many of them originally settled in places of their sponsors in Michigan, Massachusetts, Rhode Island. But later moved to California or chose tropical Florida or Hawaii as final destination. Without any government support and despite the language barrier, most of them surprisingly quickly managed to achieve a standard of living above the American average. Since the 1980’s the group define themselves as American-Indos or Amerindos. Notable Amerindos are rockstars Eddie and Alex Van Halen and videogame designer Henk Rogers.The formation of Indo-American enclaves did not occur because of various factors. As I said, they settled initially with their sponsors or in locations offered them by the church organizations. Indo-Americans also had a wide variety of occupations and skills. In this respect they were not limited to certain geographic areas. There were no forces in the host society limiting the choice of location.The first generation kept strong ties with Indonesia or the Netherlands. This phenomenon is called transnationalism. One feels to have two “homelands”. Correspondence by telephone, mail and even telegrams maintained contact. This decreased rapidly per generation. The youngest generation no longer has a direct link with the country of their parents or that of their grandparents. However, the arrival of digital communication has given a new impulse to contacts with relatives overseas. Zoom, Skype, Facetime and Teams are no longer unknown, even for the older generation. Some call it a blessing. An example of Indo-American life can be seen in the documentary by Dutchman Boudie Rijksschroef entitled The Amerindo Dream (2016). This documentary examines the experiences of the first generation of Indo-Europeans in America. In particular, an answer is being sought to the question of whether there is still an Indo-Europan identity. And if so, what significance this has for those involved. Mr. Rijksschroef has given permission to show you a piece of his documentary. We meet a first and 2nd generation Amerindo. The last one recently went to Holland to meet family…and to play music

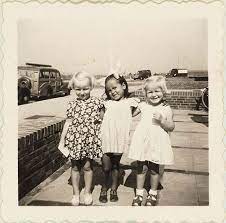

Third generation Amerindos

A vanishing culture?

Experts say that within the lifespan of the third-generation, the Indo-European community will be assimilated and disappear completely into American multicultural society.This could be the case. But there are other signs too. At a certain time new generations of immigrants start to find out or rediscover their origins and cultural background. The young Amerindos are not different in doing so. Long-established US “nationalities” such as the Irish, Italians, Russians and others went through this process. Given the small size of the community the average American does not recognize the Amerindo. They are considered Asians and treated like that. A Dutchman should be tall, blond with blue eyes, and not have the exotic appearance of the Indo-American.In any case, it is significant that Indo-Americans themselves have already taken initiatives. They converted them into organized activities. In addition to the use of new media, there are Indo-American meetings everywhere, like in Los Angeles and San Diego. These initiatives to keep the Indo-Dutch heritage alive in the United States have been given the name The Indo Project. Significant, and how seriously the subject is treated in the US, is evident from the teaching and research by the University of California Berkeley. Under the inspiring supervision of professor Jeroen Dewulf, from the Department of German & Dutch Studies, students and researchers have explored the history of the Indo-Dutch. Some of them visited the Netherlands for this purpose and met with Indo-Dutch. Particular attention is paid to the development of the Indo-American identity. Starting from their settlement here. I believe ethnic awareness is an issue in the US as well. A multi-cultural society triggers questions on roots and identity. In Holland roots-travels to Asia are getting popular. Young people seek for the places their parents and grandparents lived. Genealogical studies are trending. Archives are visited frequently. Moreover, some feel the heavy burden of the war traumas of their parents and grandparents, a multi layered trauma. They get in touch with Pelita Foundation for help or even for therapy. This raises questions on the new issue of inter-generational trauma and if it affects DNA. It’s is a dynamic debate in my country nowadays. For sure, the third generation feels the responsibility to pass through the stories of their parents and grandparents. In my hometown the memorial service of August 15, 1945 is entirely organized by women and men of the third generation. The last issue was even titled ‘Three generations connect’.

First and third generation

Pelita Foundation

Back to the Netherlands and to my work with Pelita Foundation. For those who stayed in ‘tulip and windmill country’, Pelita (a division of the National Trauma Center) has been providing services to all who suffered during the war with Japan and the following period of chaos and violence in the former Dutch East Indies. As an employee I have been involved with this foundation for over 30 years. Mostly with assisting and advising in an application for the Benefit Acts for War Victims, which is a long and difficult procedure. But also with a full care and cure program for the first, and a small part of the second generation (those who were born during or shortly after the war). Mostly people of age now.Based on more than 75 years of experience, Pelita Foundation now works within the Indo-Dutch cummunity on a new story based on participation and contribution to society. A story of resilience, resourcefulness and connection. We want to share experiences and knowledge in many ways. For those who seek a wide variety of material on Indo-Dutch and Indonesian culture and history we have developed de Cultuurkist. A digital toolbox. Pelita Foundation, together with his network of volunteers, contributes to welfare and care, of the first generation migrants from the former Dutch East Indies. Their wishes and needs should be seen and recognized. Our services, knowledge and experience with war victims, migration and adaptation offer society an excellent opportunity to respond adequately and meaningfully. In this way we create an expertise center that is also of value for institutions working with recent migrants and refugees. We do this by documenting. By participating in research. By sharing knowledge and skills. And by literally capturing stories. De Indische Podcast is an example of that.

Studio Indische Podcast

America the land of promises

What applies to the Indo-Dutch immigrants in the Netherlands also counts for the Indo-Dutch that went to the US and Canada. That is why a new series is entirely devoted to Amerindos. In recent weeks we have been recording in San Francisco and Portland.In an interview, Jane Vogel-Mantiri from Portland, Oregon, indicates that her family had to wait as long as 6 years in a 2 room apartment in Holland before they, with help of a sponsor, were allowed access to the US. Like Australia and New Zealand, the US was not waiting for these colored immigrants. And certainly not from Asia, which in those years was threatened by communism. It wasn’t until the mid-1950s, thanks to a liberal congressman, that they came to the US in substantial numbers. But they all had to have a sponsor. Under the so-called Pastore-Walter act, about 35,000 people with a background in Indonesia would receive a visa. They mostly settled in the west, not as a group, but individually. Certainly not an easy time. No government support, their diplomas were rejected, they were facing language problems, discrimination. Yet they managed to stay firm. Often by shedding their roots and origins and adopting an American lifestyle and attitude. But have they given up their Indo-European identity, or do they still cherish elements of their country of origin? And how does the average American see them: as one of the many Asian immigrants or, in the words of Tajuddin and Stern, as “Brown Dutchmen” or “Indo-American?”

Just arrived in the US

Did they become real Americans?

It’s the question I’ve asked a number of Amerindos here in California and Oregon. How they managed to survive. How they maintained an Indo-Dutch identity if the country where you were born no longer exists as such. What is that identity anyway? Is it more than a concept once formulated by the famous Indo-Dutch writer Tjalie Robinson? Jeroen Dewulf wrote an interesting article about him entitled ‘framing a Eurasian identity’. In his view the Indische culture would be nothing more than a constructed idea. Some Indo-Dutch have adopted it. True. But If you ask in the Netherlands what being ‘Indisch’ is about, you will get many different answers. Indische culture is a complex amalgam of customs, views, ideas, traditions that originated in a colonial context. That context no longer exists. But those customs and traditions evolved in the new environment into what it is today: an interesting mix of culture and folklore. Still to be seen at fairs in Holland, in entertainment, film, literature and music.And what did those first Indo-Dutch immigrants in the US pass on of that cultural identity to their children? To what extent did integration proceed differently? After all, in the US there was hardly any support like in the Netherlands with its high standard of social care, pensions, housing, education. These are subjects addressed in the new series Indisch integration in the USA.

Sources:

Tajuddin, A. and Stern, J. ‘From Brown Dutchmen to Indo-Americans. Changing Identity of the Dutch-Indonesian (Indo) Diaspora in America’ (2015)

Dewulf, J. ‘Tjalie Robinson and the American Tong Tong: Framing a Eurasian Identity in the American Sixties ‘(2022)

De la Croix, H. ‘A History of the Indos’ (Indisch Historisch) (2006)

Riel van, P. ‘Indisch inburgeren 1950-2020. A podcast series’ (2022)

Langeveld, F. ‘Van Tempo Doeloe naar The Golden State. From Tempo Doeloe to The Golden State’ (2019)

Rijkschroeff, B. ‘An experience richer. The Indische Immigrants in the United States of America’ (1989)

Leidelmeijer, M. ‘Waves of Departure. (Un)forgotten stories of Indoe-Europeans’ (2022)

Stern, J. ‘Three generations later; Examining transnationalism, cultural preservation, and transgenerational trauma in United States Indo population’ Wacana, Journal of the Humanities of Indonesia. Volume 23, Number 3 Exploring transnational relations (2022)

De Indische Podcast https://app.springcast.fm/podcast/de-indische-podcast

This article is an abstract of the lecture presented on September 12 th 2023 at University of California Berkeley.

Peter van Riel and Jeroen Dewulf