By: Degung Santikarma

|

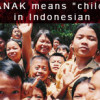

Most guidebooks say that naming in Bali is a relatively simple business. The first child is called Wayan (or Putu if the family is of high caste). The second is called Made, the third Ketut, the fourth Nyoman, and then the cycle repeats. Commoners are given the prefix “I” for males and “Ni” for females, while those of the upper castes are given caste titles: Ida Bagus or Ida Ayu, Cokorda, Anak Agung, Dewa or Gusti. A personal name such as Rai or Glebet or Sadra may also be added at the end. That’s the standard guidebook explanation. But then, the guidebook writers may never have met I Made Radio or Anak Agung Putu Carlos Santana. In the West, prospective parents often spend months poring over baby name books, trying to find a flattering moniker to suit their little darling. In Bali, naming has traditionally been much more laid-back. Birth-order names and caste titles required little thought, and even so-called personal names were rather impersonal and easy. If a mother went into labor in the marketplace, her baby might be called I Made Peken (market). If the child was born with a dented head, she might be called Ni Wayan Belek (squishy). If the baby arrived during the clove harvest, he might be called I Nyoman Cengkeh (clove). If the mother craved leafy green vegetables while she was pregnant, she might call her child I Ketut Kelor (spinach), or if she was fed up with childbearing, she might call her offspring Ni Nyoman Suba (enough). If a child was of an esteemed lineage, he would likely be given a series of titles that had less to do with his own characteristics than with his family’s status, such as Anak Agung Ngurah (pure) Gede (great). According to traditional Balinese thinking, it made little sense to go to great trouble thinking up unique names for children when they would just be changed later. Most Balinese switched names many times over the course of a lifetime. Often, as babies matured into children, their names would be modified to reflect characteristics they displayed, like Kembung (blister) for a child who would get burned playing with fire or Krebek (thunder) for a child who was afraid of storms or Glebet (crash) for a child who would often fall down. If a child was plagued by frequent illnesses, he or she would be taken to a traditional healer, who would advise the parents to change the name to confuse evil spirits. And when children grew up to have their own children, they would then be known as “father of X” or “mother of X” and later “grandfather or grandmother of X,” giving up their own names for the next generations. But when the Dutch took control of Bali in the early 20th century, names took on a whole new meaning. According to the Dutch, people should have one and only one name. Not only did this reflect their conviction that humans were unique individuals, it made it much easier to spread their modern notions of ownership and social control. Schools, bureaucracies and jails all required fixed names for those who filled them. Population records and land certificates needed something permanent in black and white. Even when Indonesia became independent, the colonial notion of naming remained. The new state was far too fond of modern marvels like birth certificates and identity cards to let Balinese continue to be casual about what they called their children. Under the rule of the Indonesian state, many Balinese began to see the name as an opportunity to express one’s cultural identity. Modern parents stopped naming their children for their misshapen heads and lack of hair, and started giving them glorious-sounding Sanskrit names like Ananda or Astakarma or modern monikers like Susi or Viki. And some people got even more creative. In my neighborhood, there are the young cousins Anak Agung Ngurah Hendrix and Anak Agung Putu Carlos Santana. And next door to them are a whole family named I Wayan Neon, I Made Radio, Ni Ketut Kopling (transmission), Ni Nyoman Lampu (lamp) and I Gede Telpon (telephone). But even the modern pressure to stick to one name couldn’t stifle the Balinese conviction that a name is meant to be modified. I Gusti Putu Palguna became I Gusti Putu Plisi (police) after demonstrating a distinct fear of the authorities. I Wayan Dempul, whose father worked at a repair shop, was named after a brand of car wax, but had his name changed to I Wayan Suprapta (good behavior) after he kept getting into trouble. I Made Dwiputra became I Made Bodrex after a brand of patent medicine that cured him of his frequent childhood fevers. I Made Darga had his name changed to I Made Deger (weird thoughts) when, as a child, he’d sit in corners talking to himself. But after he grew up, he changed his name himself to I Made Jagger, after the famed Rolling Stones frontman. Names also change when the social winds shift. I Gusti Ketut Lenin, born in the sixties when the Indonesian Communist Party’s power was at its peak, became I Gusti Ketut Lennon in the seventies, after the Party fell from power and The Beatles rose to prominence. I Wayan Tito, named for the communist dictator of Yugoslavia, became I Wayan Tiptop, after a brand of candy. And today, hundreds of Balinese babies are given names like I Ketut Dollar, after their parents’ currency of choice, or even Anak Agung Made Turis (tourist), perhaps with the hopes that the child will grow up to be a tour guide-one who can give a better explanation of just how complex naming is in Bali. |

First published in Latitudes Magazine