Indonesia’s liberal art scene attracts adventurous Australian artists

By: Kevin Murray

The sounds and sights of Punkasila are drawn from many spaces of Indonesian life – Andrius Lipsys

The sounds and sights of Punkasila are drawn from many spaces of Indonesian life – Andrius Lipsys

The history of government-sponsored cultural exchange between Australia and Indonesia is beginning to pay off. Since its commencement in 1991, the Asialink Arts Residency Program has sent almost 700 Australian artists to work and study in Asian countries. One of the program’s most curious offspring is an ongoing, Yogyakarta-based collective called Punkasila, founded by Danius Kesminas.

Kesminas embodies some of the wilder energies of the Australian cultural scene. Kesminas is a tireless Melbourne artist who is very much embedded in the art world – his exhibitions ransack modernist art history and appear in a cutting edge commercial art gallery. Yet Kesminas’ work is far from pretentious: his many projects set about attacking art’s elitism by popularising its most privileged secrets. His weapon of choice is rock music, particularly punk. His band The Histrionics perform songs about revered contemporary artists, like the Thai relational-art artist Rirkrit Tiravanija who transforms galleries into restaurants. The lyrics follow a familiar tune: ‘I don’t like Rirkrit, no, no / I love him, yeah / I don’t like your bean curd / Don’t mean no disrespect / I don’t like your tofu / If this dish is an art object.’

Kesminas shares a Lithuanian background with George Maciunas, the founder of the Fluxus movement. This international, ‘anti-art’ movement of the 1960s aimed to reinvigorate art by restoring ‘the everyday’ to artistic practice. Kesminas acknowledges Fluxus in the project Pipeline to Oblivion, which reveals an illegal, clandestine, underground vodka pipeline network in Lithuania. But in a different way, Kesminas’s work also seems quite at home in an egalitarian country like Australia, where the elitist authority of global visual arts has relatively little purchase.

The city of artisans

So we might be surprised to learn that Kesminas has commissioned work from traditional Indonesian artisans. This would seem exactly like the kind of credulous ‘politically correct’ art world project he would make the target of his satire. Despite its overt ‘worthiness’, Kesminas has been able to develop an anarchic mode of collaboration which challenges our understanding of what it is to work with artisans.

At the end of 2005, Kesminas arrived in Yogjakarta for a three month Asialink residency. His only preparation for the new culture was reading a book, The Politics of Indonesia, by Damien Kingsbury. It was a dense read, filled with acronyms. Despite their inscrutability, these acronyms would later end up being an important creative resource.

It is never clear exactly what or who Punkasila’s troops are fighting against – Andrius Lipsys

It is never clear exactly what or who Punkasila’s troops are fighting against – Andrius Lipsys

Soon after he arrived, Kesminas started hanging out at the National Art Institute (ISI). There he found a familiar scene of young rebels playing aggressive rock music. So he decided to form a band of his own and went about recruiting musicians, with immediate success. As Kesminas didn’t speak any Indonesian, they created lyrics together that were inspired by the acronyms he had read. Fortuitously, this method corresponded with a favourite local pastime of subverting words, acronyms, titles, bureaucratic talk, etc (this form of word play is known as ‘plesetan’ in Indonesian).

For example, the song TNI is based on the acronym that stands for Tentara Nasional Indonesia (Indonesian National Military) but which is sung as Tikyan Ning Idab-Idabi (Poor but Adorable, in Javanese). In a similar vein, the band adopted the title Punkasila, which is drawn from the Pancasila, the official five ideological tenets of Indonesian nationalism.

Local involvement in Punkasila expanded rapidly. A batik artist produced the band uniform in military camouflage. A wood artisan carved elaborate machine-gun electric guitars from mahogany. Much of this was well beyond Kesminas’s control, but this was exactly as he wanted it. As he puts it, he was ‘like a catalyst lighting a wick’.

Like many foreign artists, Kesminas enjoyed the freedom to make art in Indonesia. He contrasted this with the situation in a country like Australia where everything has to be paid for. ‘Over there it’s different. You just do things because you do them.’

The dangers of collaborating

Given the role of the military in Indonesian life, Kesminas was afraid their provocative repertoire would endanger his collaborators. He claimed that he ‘always had to defer to them for limits. We never did anything they didn’t want to do.’ Yet at the same time, he recognised that his role as an outsider was critical: ‘There was a nice unspoken agreement. I gave them a kind of cover, as a naïve Westerner.’ It’s hard to tell who is using who in this situation. Even though punk is an identifiably Western popular movement, Kesminas associates it more broadly with a Do It Yourself principle of cultural independence. Like the paraphernalia that was locally made for Punkasila, it represents self-sufficiency in culture and defies a reliance on imported readymade products.

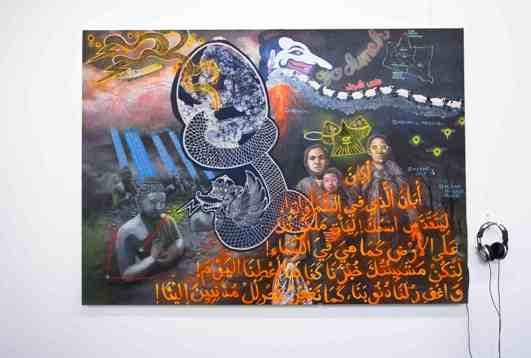

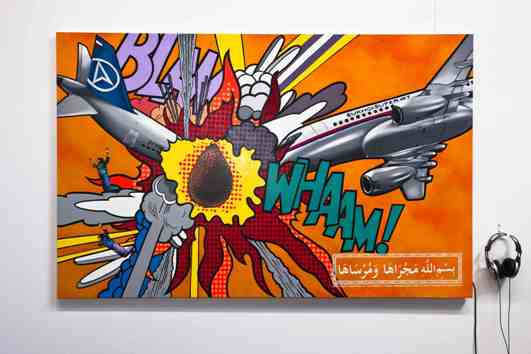

Crash Nation displayed thirteen collectively-produced paintings, each with its own soundtrack, on the theme of disaster – Arunas Klupsas

Crash Nation displayed thirteen collectively-produced paintings, each with its own soundtrack, on the theme of disaster – Arunas Klupsas

For Kesminas, the most significant complaint against Punkasila came from ‘NGO do-gooder missionary types’ who thought he was showing disrespect for Indonesian culture. Kesminas would claim that he actually more respectful by following the authentically carnivalesque nature of Indonesian street culture. According to this line, the forms we normally associate with Indonesian traditions, such as wayang puppetry, are just cultural commodities sustained for western tourists. The real life is on the street.

But in the long run, there may be problems. While it is an important detour from cultural conservatism, we need to admit that our pleasure in Punkasila is an indulgent one. It shows an image of Indonesian society that reflects back our familiar ideology of Western individualism. In the spirit of good ol’ rock’n’roll, we have a natural tendency to champion those individuals who defy authority. We join them in solidarity against local leaders – the patriarchs, warlords and ‘tin pot dictators’.

But who are the foot solders of Punkasila really fighting for in the long term? We need to think of the broader context. Countries like Indonesia face significant pressures from overseas companies to ‘open up’ for ‘development’. So why should the polygamous village elder stop you from selling your land to Monsanto? Who’s the fat old chief to say you can’t sign away royalties for your village’s traditional chant? While rock’n’roll is great for breaking things down, such as a military regime, it’s not disposed to building new structures. And nor, it seems, is Punkasila.

Crashing into the future

But the ongoing development of the collaboration puts to rest any suggestion that Punkasila is a transitory publicity stunt. In July 2012, Punkasila exhibited Crash Nation at Darren Knight Gallery, Sydney. This exhibition extended the whole concept of collaboration. Crash Nation reflected on the association of Indonesia with disaster – earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanic eruptions, floods, etc. More than 40 people worked on the project in different ways. The 13 paintings were completed collectively by more than 25 Yogyakarta-based artists. Each painting depicted a specific catastrophe, from famine and corruption to visual plagiarism. The CD contained songs each individually corresponding to one of the paintings. The paintings were a collision of styles, genres and techniques including ‘Indo-realism’, abstraction, stencil art, comic art, batik, screen and digital printing, embroidery and collage.

Due to a maritime mishap, the Crash Nation images arrived too late for exhibition at the Sydney Biennale – Arunas Klupsas

Due to a maritime mishap, the Crash Nation images arrived too late for exhibition at the Sydney Biennale – Arunas Klupsas

As sometimes happens, the Crash Nation project ended up reflecting its own subject matter. The transport of the work to Australia was delayed when the ship caught fire. The late arrival meant that the exhibition missed the peak time of the Sydney Biennale, which would have provided sales, so nothing in the end sold. This is personally disappointing for Kesminas because the aim of the show was to raise money for a purpose built compound in Yogyakarta comprising art studio, recording studio, exhibition space, bar and other facilities. But the creative drive continues, regardless of what fortune dictates. Kesminas is currently working on the next Punkasila project, a collaboration with his art-music ensemble, Slave Pianos.

There’s plenty to suspect about Kesminas. ‘So he likes the fact that they don’t have to be paid! But, hey, doesn’t he end up marketing their product in his exhibitions back in Australia?’ This line of interrogation seems to be missing the point, and indeed plays into the very stereotype of political correctness that Kesminas satirises. As far as I know, the work coming out of Punkasila has not sold. In the meantime, benefits have flowed to his Yogya-based collaborators. Kesminas raised money for his fellow band members to participate in the Havana Biennale, which profiled them on an international stage. The band has visited Australia. Sure, it all contributes to his cultural capital, but compared to other artists who use artisans like Jeff Koons, it’s relatively high on the scale of collaboration.

Indonesian collaborators

Apart from the opportunities to travel, Kesminas feels that this exchange with his Yogya collaborators has borne other fruit. In particular, he has helped them grasp what is involved in pushing their own projects into international networks. He does not claim credit for any of their post-Punkasila successes, pointing out that some of his ‘troops’, especially co-vocalist Hahan, were destined for big things even without him. But he has helped them to turn their energetic improvisations into viable projects.

The glam-metal band Sangkakala, headed by Punkasila guitarist Rudy ‘Atjeh’ Dharmawan, is one of the projects to have blossomed in the wake of Punkasila – Courtesy of Rudy Dharmawan

The glam-metal band Sangkakala, headed by Punkasila guitarist Rudy ‘Atjeh’ Dharmawan, is one of the projects to have blossomed in the wake of Punkasila – Courtesy of Rudy Dharmawan

Vocalist Uji ‘Hahan’ Handoko Eko Saputro has become a highly regarded and collectable painter who exhibited at the recent Asia Pacific Triennial at Brisbane’s Gallery of Modern Art (GoMA). He has exhibited with a commercial gallery at the Singapore and Hong Kong Art fairs. Guitarist Rudy ‘Atjeh’ Dharmawan is an excellent printmaker and draughtsperson who has recently undertaken an art residency in Myanmar. His music project Sangkakala is a glam-metal band that has performed at rock festivals in Indonesia. Krisna Widiathama combines his varied musical roles with his practice as a graphic artist, designing CD artwork and t-shirts for international metal bands. Prihatmoko ‘Moki’ Catur and Iyok Prayogo continue to work as printmakers, Erwan ‘Iwank’ Hersisusanto as a mural artist, and Terra Bajraghosa as a video artist and art lecturer, exhibiting in Japan. Woto ‘Wok the Rock’ Wibowo is a multi-media artist and web designer who has undertaken residencies in Australia and Japan and has exhibited in Vietnam. And so on.

Judging by the career development of Punkasila members, the Asialink residency has been productive for Kesminas as well as his collaborators. And this has happened in artistic forms that don’t exactly match with conventional understandings of Indonesian art. Indeed, Punkasila delivers a refreshing message: Work with artisans does not have to take the forms in which the artisans conventionally deal. It adds a pinch of salt to our sanctimony and a dash of chili in our philanthropy.

Kesminas is one of an increasing number of Australian artists working in Indonesia. The Australian sculptor Rodney Glick found working in Bali with local carvers so productive that he has now moved there, setting up a single origin café along the way. By contrast, to make an art work for a public audience in Australia encounters so many constraints, including funding priorities, legal contracts, intellectual property and risk management.

Yogyakarta, let’s go!

Kevin Murray (kevin@kitezh.com) is coordinator of the Australia India Design Platform (Sangam) and Southern Perspectives, a network promoting ways of thinking that emerge outside trans-Atlantic metropolitan centres.

Inside Indonesia 112: Apr-Jun 2013