Budi Brahmantyo continues a lineage of scientific art for which West Java’s natural resources have provided the subject

By: Hawe Setiawan

Creating visual reproductions is something everybody can do nowadays. Most people own a digital camera or have one integrated into their mobile phone. Wherever one finds oneself, all one needs to do is press a small button on the magic device, and presto! A picturesque landscape can be created.

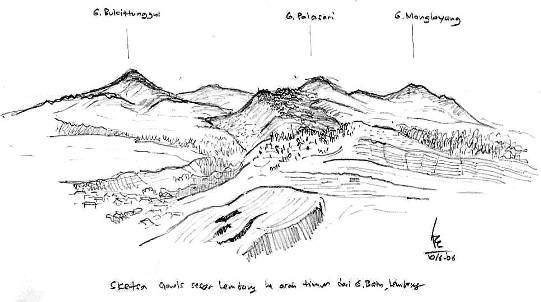

The Lembang Fault is a geological feature shaped by Bandung’s volcanic past – Courtesy of the artist

The Lembang Fault is a geological feature shaped by Bandung’s volcanic past – Courtesy of the artist

It was not always so. Throughout the nineteenth century, making an image of a landscape required skill, ability, and patience. The skill of rendering landscapes has long since disappeared from the daily lives of most people. Against this background, Budi Brahmantyo is an exception.

Dr. Brahmantyo works as a geologist at Bandung Institute of Technology (ITB). He has made many journeys throughout Indonesia, drawing natural landscapes along the way. Using simple techniques and equipment, he strikes a solitary figure as he stands motionless except for occasional movements of the head and hands. In fact, Budi is continuing a long artistic tradition that has developed within scientific circles in response to West Java’s mountainous landscape.

A life in landscapes

Budi Brahmantyo was born in the West Javanese capital of Bandung in 1962. He studied Geology at ITB until 1988. A decade later he obtained a masters degree in Geology from Graduate School of Geo and Biospheres at Niigata University in Japan. His thesis was entitled The Quaternary Geology of River Terraces at Okumiomote River, Niigata. In 2005 he obtained his doctoral degree in Geology from ITB for his dissertation The Geomorphological Development of Karangbolong Karst Mountain in Kebumen, Central Java, with Geology as a Determinant Factor. Now the head of ITB’s Geology Department, he is a true geologist.

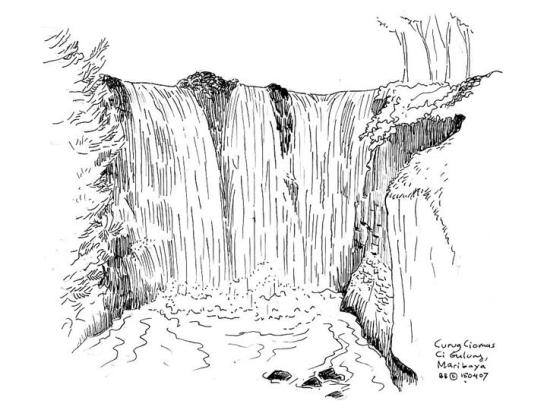

Local features such as Ciomas Falls are commemorated in Brahmantyo’s sketches as well as his tourism initiatives – Courtesy of the artist

Local features such as Ciomas Falls are commemorated in Brahmantyo’s sketches as well as his tourism initiatives – Courtesy of the artist

However, he has also enjoyed drawing since his early school years. He recalls winning a prize in a drawing competition in grade four at Muhamad Toha VI Elementary School in Bandung. It was not until 1986 that he began to seriously draw landscapes. The threshold occasion was his participation in a geological field study to the Central Javanese mountain of Karangsambung. ‘At that time, I realised that geological sketches of landscapes or outcrops were quite important for geological observations,’ he says.

According to Budi, a geologist’s skills should include sketching. But this should not be confused with the skill of making realistic impressions like those created by architects. A geologist should be able to depict the geological conditions of a place through lines and curves. If the geologist wishes to, she or he can enrich these geological sketches with attention to proportion and artistic touches. This has been Budi’s own experience. His landscape sketching evolved into a combination of professional and personal motivations. ‘I myself combine two undertakings: geological study and [pursuing my] hobby,’ he explains.

The art of geology

‘The most important thing in any geological sketch is the geological information it reveals, and not the picture it presents,’ says Budi. It is not surprising then that his methods are simple and few: observe, analyse, and sketch. He ascertains the proportion of his drawings by carefully measuring different heights and the slopes of natural landscapes. He represents the depth of the landscape through contrasts of strong and light lines, and provides accentuation with hatchings and shadings. His drawing tools are rudimentary as well: instead of using special devices like those usually used by architects, he just uses ordinary paper, pencils, eraser, pen, and clipboard. His first step is the making of a pencil draft. In the latter stages, he uses a ballpoint to edit and enhance.

Despite his emphasis on conveying geological information, Budi’s sketches have a compelling pictorial value. This emerges in his selection of sites. According to Budi, not every natural landscape is sufficiently interesting to be depicted in a geological sketch. Making a judgment depends partly on one’s perspective on the landscape. Sometimes, he climbs high in order to obtain a proper view. Natural light conditions also determine the suitability of a landscape for sketching. ‘Sometimes the need to sketch comes naturally as I walk or travel in a vehicle,’ he says.

This preparedness to sketch at impromptu moments is characteristic of his work. In his recent expeditions in Papua and Krakatau, Budi sketched landscapes despite the rocking of the motorboat in which he was travelling. The same thing happened in the Moluccas islands. He has even drafted sketches of mountainous areas from a plane.

Although Budi’s A4 sketch pad reveals images he has made of landscapes throughout almost the entirety of Indonesia, most of his works depict Bandung and environs. The city is located within an expansive volcanic basin, and for that reason, ITB has been the Indonesian centre for research in disciplines such as volcanology and geology. He is not the first expert to blend aesthetic and professional objectives in producing images of the region’s geological features. In fact, he stands in an august lineage.

Predecessors

Budi learned the skill of sketching from the prominent geologist Sampurno, who was his professor at ITB. He also studied the representation of geological features from the works of the Dutch geologists Herman Theodoor Verstappen and Antonie Johannes Pannekoek. He recalls also the work of geographer Alan H. Strahler and his brother Arthur Newell Strahler entitled Introducing Physical Geography as an influence. This work inspired Budi to study the visual aspects of the natural landscape.

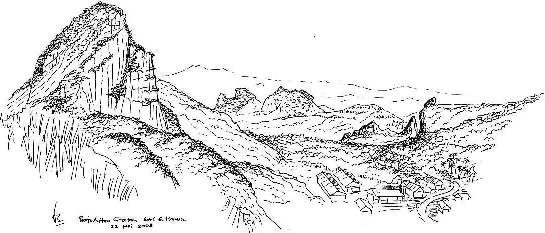

Geological details, such as those of the Citatah Crater, are finely rendered in Brahmantyo’s sketches – Courtesy of the artist

Geological details, such as those of the Citatah Crater, are finely rendered in Brahmantyo’s sketches – Courtesy of the artist

Based on their research and exploration of the natural features of Indonesia, these men have produced a large corpus of images in diverse media. By far the best known of these scientist-artists was Franz Wilhelm Junghuhn (1809-1864). Junghuhn was a German-born Dutch naturalist who travelled through parts of Sumatra and the whole of Java. From his base in Bandung, he was involved in various scientific and agricultural projects for the Netherlands Indies government. He also produced a distinctive body of images of Indonesian landscapes that was shaped by progressive humanitarian thinking characteristic of many nineteenth-century naturalists.

Geotourism

Budi’s concern for the environment motivates his involvement in geotourism. This is a form of tourism that appreciates the geographical characteristics of tourist destinations. This branch of tourism has developed in Indonesia since a workshop on the subject was organised in Bandung in 1999.

Geotourism is not widely popular, but Brahmantyo is one of the few concerned to develop it. His teaching at ITB includes a course on the topic, and, along with like-minded people, he encourages public awareness of the Bandung Basin, drawing attention not just to its geological aspects, but also to environmental issues such as the limestone mining in Citatah, the flooding of the Citarum River, threats to archaeological sites, the instability of the Lembang Fault, landslides, and the risk of volcanic eruptions. As he explains, ‘Geotourism is a way to convey geological issues to general public. It is actually intended to make people aware of environmental conditions in Bandung. People need to know and care about the problems that are arising and will arise.’

Out of his deep concern with the environmental condition of Bandung Basin, Brahmantyo and his colleagues created an excursion program called Geotrek. College students, journalists and others have joined the tour over the past few years. On these journeys, Brahmantyo and his friend the geographer T. Bachtiar inform tour members about geological and geographical issues related to the places they visit, such as Mount Tangkubanparahu in the northern part of Bandung, and Pawon Cave in the western part of the city. ‘I always encourage the participants in Geotrek to capture natural phenomenon not only through simply observing, taking photographs or writing, but also by drawing sketches,’ he says.

Budi’s sketches have not yet been exhibited, but many of them can be found in publications. Some have appeared as illustrations in his books such as The Warning from Pawon Cave (2004, published with editor T. Bachtiar), Geology of the Bandung Basin (2004), and Geotourism in the Bandung Basin (2009, with co-author T. Bachtiar). Other sketches were recently printed in Geomagz, a Bandung-based magazine published by a body within the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources. He is also planning to publish a compilation of his sketches.

Budi belongs to a small but distinctive space for image production in Indonesia. Indonesia’s natural features have attracted the attention of scientists for whom the creation of visual images has been an aspect of their professional work. At the same time, their reproductions frequently resonate with artistic genres of landscape art. The legacy of Budi Brahmantyo, Junghuhn and others consists not only of a body of visual images that have scientific as well as aesthetic value. It also maintains the fast disappearing skill of landscape drawing.

Hawe Setiawan (hawe_setiawan@yahoo.com) is a freelance columnist and lecturer at Pasundan University, Bandung. He is completing a doctoral dissertation at ITB on the works and thinking of Franz Willhelm Junghuhn.