By: Ward Berenschot and Darmawan Purba

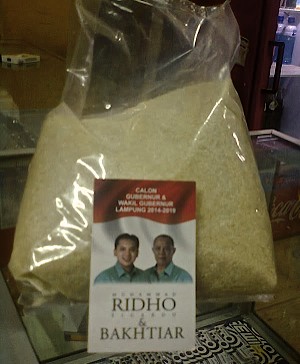

Ridho’s campaign sugar- LampungOnline: http://www.lampungonline.com/2014/03/bagi-gula-cagub-cawagub-lampung-ridho.html

Ridho’s campaign sugar- LampungOnline: http://www.lampungonline.com/2014/03/bagi-gula-cagub-cawagub-lampung-ridho.html

On 9 April, Ridho Ficardo became the new governor of Lampung, Sumatra’s southern-most province. At first glance, the 33 year-old seems an odd choice as he lacks both charisma and government experience. But he does possess one winning feature: he is the son of one of the directors of Sugar Group Companies (SGC), the producer of the ubiquitous Gulaku sugar.

Sugar Group’s financial support has enabled Ridho to spend lavishly during his campaign. True to his campaign slogan, ‘giving and serving [to] the people of Lampung’, Ridho made the gubernatorial elections a lavish feast. Trucks, full of sugar, were driven up to villages through Lampung to execute a massive flood of two-kilogram sacks of sugar adorned with Ridho’s picture. This, followed by a string of music concerts, puppet plays and what was reportedly a direct distribution of Rp.50,000 per voter ensured the consistent rise of Ridho’s name in the polls. In the end, he won 44 per cent of the votes, well ahead of his competitors. This achievement had cost, according to estimates of interviewed observers, up to Rp.500 billion (US$43 million).

This money served to cement SGC’s already considerable political clout. Sugar Group has long been giving donations to politicians. Since 2011, the company has been bankrolling election campaigns for district heads, which led to the election of its candidates in Tulang Bawang and Tulang Bawang Barat.

Renewing a land lease

It is no coincidence that these districts have large plantations owned by Sugar Group. The company stands to gain considerably from having put their men in power. The main reason for Lampung’s extravagant sugar feast is the upcoming expiration of SCG’s 30-year land lease (HGU) for some plantations. Given the enormous bribes that a renewal of such a land lease typically involves, SGC will probably recoup most of its campaign expenses now that Ridho is the person authorising these renewals.

SGC is also involved in a number of land conflicts with other companies – such as the long-standing legal battle with the Salim group over both land and factory – as well with villagers. In 2012, villagers in Tulang Bawang staged a big protest against SGC for taking their land and cutting off the access to their village. With the governor as well as local district heads now their allies, SGC will no longer be bothered by such matters. SGC is likely to use its ‘friendly’ politicians to acquire licences for more land to expand its plantations. The already tense nature of land tenure in Lampung suggests that Ridho’s election may well trigger a new wave of land conflicts.

Ridho Ficardo hardly hides his allegiances. The 16-line election program on his website suggests that serving Sugar Group is his main goal: ‘the potential of the agro-business in Lampung is hampered […] by weak infrastructure, security concerns and pungutan liar (‘wild fees’, i.e. rent-seeking). What should we do to solve this? We need to elect a leader who has the solutions.’ Indeed, for SGC, Ridho embodies the solution to yet another big operational challenge: the rampant rent seeking that has plagued the company for years.

Bureaucrats and politicians have been extorting money from the company by threatening to take up (and make up) irregularities in SGC’s land use and production. SGC is the predominant corporate presence in a relative economic backwater. It also works within a weak and contradictory legal framework regarding land use. This could mean that SGC is vulnerable to being used ‘like an ATM’ by enterprising individuals at all levels of government. Ridho is now expected to be more firm in dealing with such practices. In fact, that is what informants sympathetic to SGC have been arguing – that SGC put Ridho in power to ‘clean up’ and ‘professionalise’ state institutions.

Locals drive to a Ridho campaign rally- Author’s collection

Locals drive to a Ridho campaign rally- Author’s collection

An eager embrace

Lampung’s sugar-coated elections illustrate how Indonesia’s democratisation process is driving business and politicians into each other’s arms. Doing business in Indonesia used to depend on having good contacts. During the New Order, tycoons could amass large fortunes by exploiting their connection to Suharto to obtain licences and exemptions. But the hope was that reformasi would change the oligarchic character of Indonesia’s politics and distribute power more evenly. Some early reforms, such as a new forestry law, a law on labour unions and a commitment to recognise common land rights, suggested big (agro-) businesses could no longer trample on the rights of Indonesia’s citizens. But, as various observers have now pointed out, democratisation has merely changed the strategies of Indonesia’s economic elites, not their dominance.

SGC advertisement congratulating a local Bupati on this election win- Author’s collection

SGC advertisement congratulating a local Bupati on this election win- Author’s collection

While entrepreneurs needed to cultivate contacts with influential bureaucrats during the New Order, now, they buy their influence by supporting the election campaigns of politicians – or by becoming one themselves. Because of the spiralling costs of running an election campaign, politicians can hardly forego such corporate support. A successful political career requires one to be either a businessman or have the support of one.

This intimate embrace between business and politics is largely self-reinforcing. As businesses realise that political contacts are vital for obtaining licences and for avoiding the ubiquitous rent seeking, they face strong incentives to engage in secret or not-so-secret deals with political hopefuls. Such considerations drove Sugar Group to support politicians. The company does not really want a more professional bureaucracy when it comes to issuing new licences. A bureaucracy that implements policies and laws in a universal, impersonal way would not enable Sugar Group to recoup the money it spends on election campaigns. To recoup these costs, Sugar Group expects its politicians to intervene in bureaucratic procedures to bend rules and regulations in their favour. In this way, such deals are in fact weakening state institutions and diluting the relevance of rules and policies.

In order to honour their commitments to supporters and campaign funders, elected leaders constantly undermine and evade bureaucratic procedures. The resulting weakening of state institutions further reinforces the dependence of entrepreneurs on politicians as they have little assurance that rules and policies will be applied in a predictable fashion if they lack political contacts. In this sense, Sugar Group’s business strategy is self-defeating. As long as economic elites (like SGC’s directors) use their contacts to circumvent regulation, their political meddling will not lead to the professionalisation of state institutions or the stamping out of rent-seeking practices.

Public disillusionment and electoral sweeteners

The overlap between politics and business is self-reinforcing in yet another way. Voters see the large fortunes that politico-business coalitions are amassing by granting licences and contracts to each other. They realise that politicians’ promises of regulatory and policy change are often empty, because voters see how elected leaders do not abide by regulations when pressured by their corporate friends. In this context, it is no surprise that many voters trade their votes for money (or sugar), seeing that such sweeteners might be the only benefit they can realistically expect from their politicians. Observations of the campaign during the legislative elections on 9 April suggest that vote buying has become very common. Voters are becoming increasingly pragmatic in their dealings with politicians. The irony is that this disillusionment with politics and the resulting expectation of money and gifts end up facilitating the continued dominance of economic elites, as the spiralling costs of campaigning makes politicians dependent on wealthy donors.

At present, there is little scope for voters to punish politicians for engaging in backroom deals with companies. Voters generally do not know which companies are funding their candidates. Politicians are required to report on their campaign funds and expenses. However, as there are no mechanisms to check their veracity, these reports have become meaningless administrative exercises. Furthermore, even while Sugar Group’s involvement in Lampung’s gubernatorial elections was rather blatant, local journalists rarely dared to make explicit mention of the company for fear of reprisals and withdrawal of advertisements. As a result, voters do not really know what business interests they might actually be supporting with their votes. The farmers who protested against the Sugar Group in Tulang Bawang in 2012 might have voted for Ridho simply because the role of corporate backers rarely enters public debate.

More transparent campaign financing

One solution might be, as Marcus Mietzner argues in his recent book on Indonesia’s political parties, to increase state funding for election campaigns. This would reduce the dependence of politicians on corporate donors. But it would hardly eliminate it.

Initiatives are also needed to improve the transparency of campaign financing. Latin American countries are showing that this is not impossible. Through a combination of legal reform and painstaking research, a number of Latin American NGOs are succeeding in publicising politicians’ sources of campaign funds. Their websites have become important source for journalists, enabling them to expose the privileges granted to campaign donors. A replication of such efforts in Indonesia could enable voters to better scrutinize their politicians and, ultimately, loosen the ties between business and politics.

Ward Berenschot (ward.berenschot@gmail.com) is a researcher at KITLV Leiden working on clientelism and citizenship in Indonesia. Darmawan Purba (yuanren_purba@yahoo.com) is a political scientist at the University of Lampung